INTRODUCTION: THE INDUS CIVILIZATION (e. B, C. 3000-2000)

THE VEDIC CULTURE (c. B. C. 1500-800.)

Many efforts have been made to express in a few words the precise meaning of Architecture and its relation to the human experience.

Lethaby has approached the subject most nearly in stating that “Architecture is the matrix of civilization’’. To such a definition it may be added that viewed historically architecture remains as the principal visible and material record, through the ages, of man’s intellectual evolution.

Each great cultural movement has made its own particular contribution to the art of building so that the aspirations of the people and even their way of life stand revealed in substantial form for all to see.

And in India man’s ideals have found expression in numerous noble monuments showing that few countries possess a richer architectural heritage.

To the student the value of these productions need no emphasis, for from such achievements it is possible to reconstruct much of the past and to visualize the social and political conditions of the country as phase succeeded phase and one period merged into another.

In each of the major historical developments of architecture there is one basic principle underlying its conception and one which is supremely distinctive. With the Greeks this was refined perfection; Roman buildings are remarkable for their scientific construction: French Gothic reveals a condition of passionate energy, while Italian Renaissance reflects the scholarship of its time. In the same way, the outstanding quality of the architecture of India is its spiritual content.

It is evident that the fundamental purpose of the building art was to represent in concrete form the prevailing religious consciousness of the people. It is mind materialized in terms of rock, brick, or stone.

This characteristic of Indian architecture is emphasized by the treatment of its wall surfaces. The scheme of sculpture which often covers the whole of the exterior of the building is notable not only for the richness of its decorative effect but for the deep significance of its subject matter.

Here is not only the relation of architecture to life but transcendent life itself plastically represented.

Carved in high or low relief is depicted all the glorious gods of the age-old mythology of the country, engaged in their well-known ceremonials, an unending array of imagery steeped in symbolism, thus producing an “Ocean of Story” of absorbing interest.

In view of this character for rich treatment it is strange to find that the earliest known phase of the building art in India, recently excavated, discloses a style of structure which has been described as aesthetically barren as would be the remains “of some present-day working town in Lancashire.”

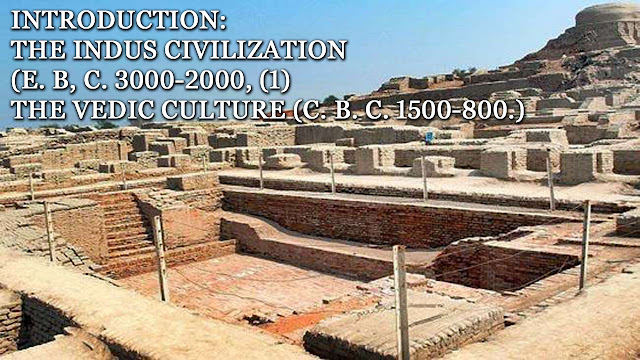

This development in the dawn- age of the country has been designated the “Indus Civilization”, as the records of its culture have been found buried in the soil of the regions bordering on the river Indus.

A comparison of these remains with those of other countries of which the chronology is known, as for instance Mesopotamia has indicated that the Indus Civilization was in a fairly matured state as early as 3000 B.C, so that its origin may go back to a still more remote age.

Two separate sites have so far been excavated, but there are mounds and other evidence which imply that it extended over a considerable portion of north-west India and even beyond, thus embracing “an area immensely larger than either Egypt or Sumer.”

Whether it was distributed over the remainder of the subcontinent remains to be seen, but there is an opinion “that this culture spread to, even if settlements were not actually made in, the Ganges valley”.

The two sites at present explored are at Mohenjo-Daro (Sind, “the Place of the Dead”) in Sind, and at Harappa in the Southern Punjab which disclose the foundations of two cities in numerous well-defined strata, denoting that they flourished over a long period.

Although the investigations have revealed a culture in which the buildings of its people had no great artistic value, the finished quality of the materials employed, the high standard of their manipulation, and the stability of the construction as a whole is astonishing.

In the first place the builders of these cities had acquired no little experience of town-planning, as proved by the methodical manner in which they were laid out with straight streets at right angles, the main thoroughfares running almost due north and south, east and west.

The principal buildings were also very regularly orientated having their sides towards the cardinal points; while each city was divided into ways for protective purposes.

All the walls of both houses and public buildings were constructed with a pronounced batter or slope, but it is in the substance and preparation of these edifices that the artificers showed such exceptional knowledge.

In both cities, the buildings were composed entirely of burnt brick, which in size were on an average rather larger than the common kind used in the present day.

They were laid in mud-mortar in what is known as “English bond”, that is a course of stretchers alternating with a course of headers, care being taken to break the joint where necessary, the entire process indicating that the Indus builders were thoroughly experienced in the technique of the bricklayers* craft.

This method of construction applies mainly to the foundations and walls of the buildings, but as these were very substantial it seems probable that they were two or more stories in height.

The upper stories were composed largely of wood, the roofs being flat and built of stout beams covered with planking finished with a top-dressing of beaten earth.

No instance of the use of the truce arch has been discovered, openings being generally spanned by wooden lintels, but several instances of the corbelled arch formed by oversailing courses of brick have come to light.

In view of the persistence with which the Indian builder until the late medieval period clung to the latter method of bridging a space, this fact is significant.

Of the different types of building comprising these cities, dwelling houses both large and small predominate, but there are a certain number of more important edifices, built for various purposes.

Among them may be identified large structures probably used as market halls, store-rooms or offices; another arranged around two spacious court-yards which may have been a palace; several halls possibly for religious usage, and at Mohenjo-Daro a very complete bathing establishment.

Yet although all the buildings were constructed of materials and in a manner far in advance of their time, their style is one of such stark utilitarianism that they cannot aspire to be works of architecture; in effect, they represent a very practical form of building construction.

There is of course the possibility that on these edifices some kind of mural decoration may have been applied, such as carved wood or color, but if so this has completely disappeared.

The impression therefore conveyed by these remains is that the country was populated by a busy community of traders, efficient and precise in their manners and customs, but devoted to a life of materialism, and deficient in that aesthetic instinct which demands and naturally creates an artistic environment.

Subsequently a third site was explored, that of Chanhu-daro, eighty miles south-west of the better-known Mohenjo-Daro, in an effort to find a site that would give more information as to the beginnings of this civilization other than those already investigated.

Alternatively, there was also the prospect of throwing additional light on the dark period between the disappearance of the Indus culture and the entry into India of the Aryan-speaking peoples, presumed to be about 1500 B.C. The results were, however not especially informative.

The strata at Chanhu-daro seems to go a little further back than the other sites, but it was deserted about 2000 B.C. This part of the country must at the time have had its attractions, but it appears to have had the great disadvantage of persistent floods which eventually forced its population to move.

As a whole, the inhabitants of these parts seem to have been a migration from the west—the direction of Iran—and when they moved it was probably eastwards, where they would have become assimilated into a yet older population and thus have lost their identity.!

The “Indus Civilization” probably declined sometime early in the second millennium B.C., for the excavations reveal that its cities were then falling into a state of decay.

At a later date, the deserted appearance of this part of India was remarked on by a Greek writer who relates that here were “the remains of over a thousand towns and villages once full of men”.

In spite of its virile character and the experienced methods of construction that were achieved at this early age in India this powerful and well-founded culture died out without appearing to influence in the slightest degree the nature of the building art that followed.

It is possible that some great cataclysm cut across the current of events making an entirely fresh beginning necessary.

Some such interruption is not unknown in the world’s history as the advance of civilization is not always a steady progression but may become an intermittent phenomenon.

A case in point is that of the Myeeanized Greeks of the thirteenth century B.C., and at a much later dale the Romanized Gauls, who in both instances relinquished their methods of permanent construction to revert lo temporary habitations of Wattle and daub.?

As in Europe so in India. After the decay of the Indus Civilization when the art of building again comes into view, this no longer consists of well laid out cities of finished masonry but takes a much more rudimentary form of humble village huts constructed of reeds and leaves and hidden in the depths of the forest. The culture of the people was beginning again.

The exploration of origins reveals the motive power which gives an art its initial impetus, and it is in the primitive culture of a people that these origins are to be found.

Primitive art is the matrix of the higher and is the source from which more advanced forms are derived.

The Vedic culture of India provides the material for a study of the first efforts at building construction, when man’s efforts were made in response to a need, and before any ideas of architectural effect were conceived.

This culture, which produced the elementary type of forest-dwelling referred to above, appeared probably towards the end of the second millennium B.C.; it was the outcome of the great Indo-Aryan migration from the north-west, and which in the course of time laid the foundations of the Vedic Age.

That those responsible for this culture were unrelated to the people of the Indus civilization seems fairly clear, as there was a wide difference in the conditions under which each of these populations existed, in their mode of life, and notably in the type of building produced by this method of living.

On the one hand, the inhabitants of the Indus region, as already shown, were mainly traders and town-dwellers, while on the other hand the Vedic people were of the country, wresting their living from the fields and forests.

As far as is known the latter were originally nomads, an offshoot of an immense and obscure migration, who, on settling down in the plains of India, became partly pastoral and partly agricultural, having as their habitation’s rudimentary structures of reeds and bamboo thatched with leaves.

It was not therefore from the fine houses forming the towns of the Indus civilization, but from such temporary creations as these and the various simple expedients devised to meet the needs of the forest dwellers that Indian architecture had its beginnings.

Its foundations were in the soil itself and from these aboriginal conditions it took its development.

From a variety of sources, it is possible to visualize the kind of building that the early settlers found it suitable for their purpose.

Considerable miscellaneous information is contained in the Vedas, those lyrical compositions which have been preserved through three millenniums, while ingenuous vignettes depicting the life of the times are carved in bas-relief on the stupa railings of Barhut and Sanchi.

In addition, there is the significant character of the subsequent architecture which reproduces in many of its aspects the type of structure from which it originated. Supplied with this material we see the people living in clearings cut out of the primeval forest, just as some of the small cultivators at the present time in India, notably in parts of Bengal, still, carve their homesteads out of the bamboo jungle.

But these early immigrants had to protect themselves and their property from the ravages of wild animals, and so they surrounded their little collection of huts (grama) with a special kind of fence or palisade.

This fence took the form of a bamboo railing the upright posts (tabha) of which supported three horizontal bars called suchi or needles, as they were threaded through holes in the uprights.

In the course of time this particular type of railing became the emblem of protection and universally used, not only to enclose the village, but as a paling around fields, and eventually to preserve anything of a special or sacred nature.

In the palisade encircling the village, entrances also of a particular kind were devised. These were formed by projecting a section of the bamboo fence at right angles and placing a gateway in advance of it after the fashion of a barbican, the actual gate resembling a primitive portcullis (gamadvara).

Through the gamadvarasthe cattle passed to and from their pasturage, and in another form it still survives in the gopuram (cow-gate) or entrance pylon of the temple enclosures in the south of India, But, more important still, from the design of the bamboo gateways were derived that characteristic Buddhist archway known as the Torana, a structure which was carried with that religion to the Far East, whereas the torii of Japan and the piulu of China, it is even better known than in India, the land of its origin.

Counting Reading:

Read About Famous Urdu Poets: