Most Famous Paintings By Edouard Manet

Search Results

Web res

Music in The Tuileries Gardens

|

| Music in The Tuileries Gardens |

per class background, was part of this refined milieu. Its title notwithstanding, there is no hint of a musical instrument in the painting. The scene’s focus are the figures crowded between the trees, their gazes, and their conversations.

Baudelaire had recently written the essay “The painter of Modern Life,” later published in 1863, to which Manet’s painting appears to be intended as the painted version.

Oth- er disturbing factors were the rapid style, details that were barely sketched, and features that go perfectly with the sonorous impression of a busily chatting crowd.

The effect, which opened the door to modern painting, was clearly intentional; in fact, though he had made studies on-site, Manet paints” ed the work entirely in his studio.

Manet had ultimately created a daring portrayal of modernity, of that Parisian life soon to be celebrated in a short work by Offenbach, with the lyrics “Everything tums, turns, turns… Everything dances, dances, dances. “

|

| Lola De Valence |

Images of Spanish dancers, in particular, had so much success that even the Realist painter Courbet had painted work in 1851 that is very similar to Manet’s. However, it is known for certain that Manet had never seen it, indicating that the similarities are due to the similar sources of Goya’s paintings and popular prints.

Lola, dressed in the Andalusian costume in which she performed, is shown in a pose with one foot in front to the other and a closed fan in her hand, ready to go on stage.

Against the tenants of official painting, these details are not minutely rendered with a wealth of well-defined details; instead, they are barely sketched through the juxtaposition of patches of color.

For these reasons, the painting caused a stir when it was exhibited in 1863 at Manet’s individual show at the Martinet gallery. It was deemed by Mantz, the Gazette des Beaux-Arts critic, a “caricature of color.”

Baudelaire celebrated Lola in a quatrain, which became an immediate object of parody. “Amongst the many beauties one sees everywhere, I well understand, friends, that desire hesitates to choose/ But one sees sparkling in Lola de Valence/ The unexpected charm Of a pink and black jewel,” words which, in fact, poorly pair with the portrait of the rather masculine woman painted by Manet.

|

| The Street Singer |

Manet was struck by a woman who was coming out of a modest cabaret, raising her dress and holding a guitar.

He asked the singer to pose for him. When she refused, he portrayed Victorine Meurent, his favorite model at the time.

To the scene of original inspiration, Manet added a wonderful still life of cherries in an open paper that Victorine brings to her mouth with a weary gaze lost in thought.

Beyond the green door behind her, we glimpse the smoky interior of the cabaret.

Manet chose to make a life-sized portrayal of a common subject, giving it the stature of an official portrait, which predictably drew fire from the critics. Manet was accused of having lost the righteous path undertaken with The Guitarist.

Traditional critics were vexed by this characteristic, seeing a vulgar portrayal in the painting, unmitigated by the pathos common in such contemporary scenes.

Zola astutely observed that Manet treated his figures like still lifes, paying more attention to the play of forms and colors than the soul of his characters.

Indeed, Manet seemed more attracted by studying the work’s formal quality, perhaps influenced by the two-dimensional figures turned into contours in Japanese prints than its social implications.

|

|

Mademoiselle V…

In the Costume of an Espada

|

Despite the semblance of realism, the painting is an explicit fiction. The title declared that the matador was impersonated by a woman instead of a man and, what’s more.

A Frenchwoman posing as a Spaniard. The shoes are completely un. suitable for bullfighting, and the great distance between the size and rendering of the figure in the foreground and the background gives the impression of a kind of a photomontage.

While the pink cape seems like a piece of extraordinary modernity to us today, the reviewers of the time saw it as an unfinished sketch, a judgment they applied to the entire painting.

Again Manet concentrated on the work’s formal qualities, orchestrating a sophisticated harmony of colors that combined the artist’s characteristic brilliant—even luminous—black, with the pink, yellow, and white patches of the costume’s smaller details.

This absence of organic qualities is not the mark of a lack of skill; it is, rather, a sign of his exclusive interest in studying and juxtaposing colored masses.

The work was purchased by the dealer Durand-Ruel in 1872 for 4.000 francs. He sold it two years later to the singer Faure for and bought back it for twice that in 1898; at the end of the same year.

the American collector Havemeyer paid 15, 000 francs, and later donated the collection to the Metropolitan Museum.

|

| The Luncheon on the Grass |

Two Men in contemporary clothes converses in a field next to a nude woman, while another nude woman is bathing in a stream. lunch is placed between us and the nude model who gazes openly in our direction.

Proust tells us that the painter was inspired by an actual scene (a group of women taking a bath in the Seine). undoubtedly filtered through Giorgione and Titian’s Concert Cham. pétre and a Marcantonio Raimondi engraving after Raphael’s Judgment of Paris.

The portrayal of the nude was certainly nothing new in French art. From the venerated Ingres to the Salon’s celebrities, it was, in fact, a recurring theme, as well as a subject of study at the École des Beaux-Arts.

Manet’s reference to great masters in Le déjeuner did nothing to legitimize the work and made it seem even more scandalous, a desecration of a noble model, even sullied.

Hamilton unequivocally expressed his opinion that a disgraceful Frenchman had translated Giorgione into modern realism and horrible modern French clothes in place of the elegant Venetian costume.

The contemporary setting, which removed the hypocritical support of the historic guise, was unacceptable. Stylistically speaking. the work, related to Courbet’s realism, was also shocking.

The lack of 0t definition to the forms, working through color alone, was considered absolutely insolent.

Read Also: K. S. Kulkarni | Biography | Life | Artworks

|

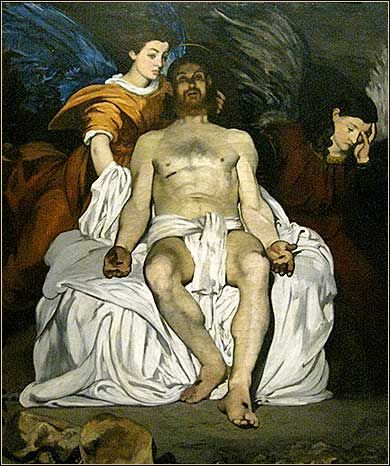

| Dead Christ and the angels |

This time, more than the subject itself, it was the execution and the choice of the colors that inflamed sensibilities.

The dirty white of the cloth on which Christ is laying comes up against the body’s shadowy pink, which many critics interpreted as mere dirt.

The realism of the dead body seemed like open blasphemy, a caricature of all that is holy, which took no consideration of the spiritual aspect of the Savior’s death.

Moreover, the Life of Jesus by Ernest Renan had been published the year before, in which the author suggested seeing the supernatural events narrated in the Gospels as fully explicable episodes.

It is also possible that the painting was an indirect response to the theories of Gustave Courbet, the leader of the realist school.

At the end of 1861, he had addressed a well-known open letter to some students of the École des Beaux-Arts, urging them to depict only visible subjects.

Several writers reported Courbet’s sarcastic comments about the painting, of which he especially criticized the angels, with their colored wings and human aspect.

Manet was certainly not in agreement with this colleague, yet it is unlikely that this was the painting’s origin.

The Dead Christ is another tribute to, and free interpretation 01, the works of Mantegna, Veronese, and Tintoretto.

|

| Vase of Peonies on a pedestal |

The fairly large painting in the Musée d’Orsay shows a small decorated ceramic vase, typical of the reign of Napoleon Ill, with a bouquet of pink and dark red flowers, explosions of light, and luminous color in the midst of the dark green shapes of the leaves. A stem has fallen on the table, on which a pile of pink petals also lies.

The splendid bouquet, which expands in all directions, stands out powerfully from the dark, homogenous background with the tone of its color and the vivacity of its execution.

At the time, peonies were a fashionable flower, recently imported from the East. Manet dedicated an entire series of paintings to them.

When Vincent van Gogh moved to Paris and started to paint floral still lifes he was struck by Manet’s painting, in which he admired the refined chromatic contrasts and thick brushstrokes.

|

| Branch of White Peonies with Pruning Shears |

Manet was a specialist in still lifes despite having painted few as in. dependent works. He preferred to include them in larger compositions, though giving them considerable importance and space, as in the bouquet of flowers in Olympia and the remains of the lunch in Le déjeuner sur l’herbe.

Paying his habitual close attention to the juxtaposition of colors, Manet chose a black and brown background, darker than that for the vase of flowers from the same period. Against this background, the two intensely luminous white peonies stand out with extraordinary power.

Delicate shadows of blues, yellows, and grays help create the impression of volume. To balance the color harmonies Manet included a few green leaves, almost as if they were random.

Manet placed the work to his friend Champfleury, a critic and realist novelist. Subsequently, in 1899, Count Isaac de Camondo bought it for 1,627 francs, a considerable amount for such a small painting; he donated it to the Louvre in 1908.

|

| Fruit on a Table |

Artists drew particularly from works by Chardin, whose simplicity and natural elegance made him admired in the late nineteenth century.

He was more interested in the general effect, the study of colored masses, the play of light, and the sculptural construction of objects through color.

Manet wanted to show the public what he perceived, using the word “impression” to these ends, continuing, “And the grape! Do you want to count every single grape? Certainly not! What matters is the tone of the light amber and the dust that shapes them and softens them at the same time. It is the luminosity of the tablecloth…”

The scene’s rhythm is marked by the effect of the folds, rendered ‘vibrant by a dynamic light that generates small pockets of shadow.

Manet harmonizes the depiction with varying tones of green, introducing the vibrant note of the peaches, and two particularly luminous reflective objects. the glass and silver knife, to fill the empty space on the right.

Read Also: B.C. Sanyal | Biography | Life | Artworks

|

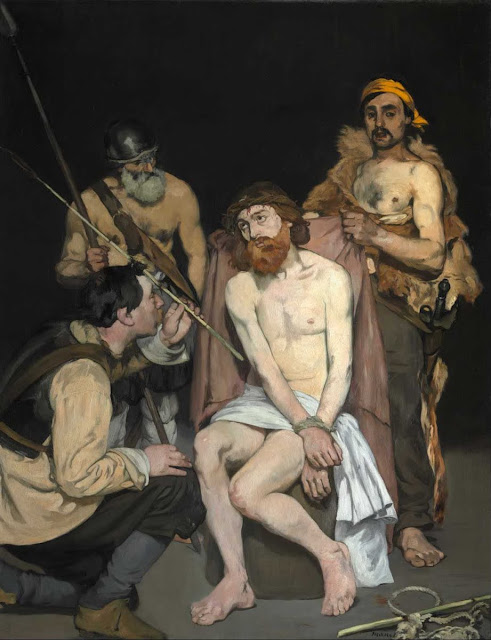

| Christ Mocked |

Christ looks more human and mortal than ever, powerless in the face of his executioners.

The choice to exhibit the holiest figure of the Western world together with a depiction of a prostitute only added fuel to the fire of scandal, giving Manet the sudden and unwanted notoriety as an ignoble artist. According to his friend Duret, people turned around in the street to stare at him.

At any rate, as he had for Olympia, Manet took inspiration from paintings of earlier centuries, especially the Dutch painter Anthony Van Dyck, and likely Titian as well, though his execution still was influenced, as always, by Velazquez.

Manet removed all details of setting—including only a small still life—to concentrate the scene on the figures, arranged on two crossing diagonals, lingering on the description (though in his usual quick manner) of the details of the clothing, the shirt with the rolled-up cuffs of the kneeling figure, the metal helmet of the older man, and the fur worn by the man standing to the right.

This man, rather than Jesus. gazes at the viewer, soliciting their emotional participation.

|

| Reading |

Manet depicted his wife here with a lightweight, gauzy dress of white muslin, sitting on a so. fa of the same color. A balcony can be glimpsed through the Similarly white and transparent curtains.

Two years earlier, the American painter James McNeill Whistler, a friend of Fantin-Latour, had joined Manet in creating scandal at the Salon des Refusés with a painting depicting a standing girl, known thereafter as the Symphony in White (Washington, National Gallery).

In 1852, Suzanne had had a son, Léon, who lived with them both, but bore his mother’s last name and called Manet, whose paternity has never been verified, his stepfather.

The difference in style between the two figures in this painting gives the impression that Manet returned to the painting at a later time, introducing the figure of Léon reading, and probably the plant on the left to balance the dark mass.

An earring, almost invisible amidst the strands of hair fallen loose from the bun helps frame her face, while the plant’s leaves seem to replicate the pose of her right hand relaxed on the sofa’s armrest.

|

| Angelina |

Since his earliest years, he had been a great admirer of Spanish painting, especially that of the great eighteenth-century artist Diego Velåzquez, as well as the tormented painter Francisco Goya, who lived between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

He had painted several scenes connected to bullfighting (without ever having seen one) and folk fig. ures, such as The Guitarist and Lola de Valence.

Though he continued to admire the concise style of the two painters, he would abandon Spain as a repertoire of images, and dedicate himself to portraying modern Parisian life.

The girl, who is young but not beautiful, adorned with the traditional black veil, is shown in half bust, standing behind a wrought iron railing, likely an early hint of what Manet would develop a few years later with The Balcony.

She looks sideways out of the painting, holding a fancy black fan in her hand, an attribute which would later be given en almost exclusively to Berthe Morisot.

The impression of the Spanish painter’s works must have been particularly strong in Manet after his recent visit to the which houses the most important Velåzquez collection.

|

| Portrait of Zacharie Astruc |

Astruc was a passionate connoisseur of Spain and Japan, and he planned Manet’s 1865 travel itinerary through the land of Velazquez.

The other hand, resting on the chair’s armrest, is barely sketched, with the intentional effect of an out of focus object that goes unobserved at first glance to let the face be perceived before it.

In a carefully planned jumble, Manet painted both old and new books, including a Japanese album on prominent display with its black cover.

Historians have long puzzled over the domestic scene, discarding the theories that it could be a second room or a reflection in a mirror, It is more likely that Manet showed a painting resting on the table’s edge, in which his friend’s wife is portrayed.

Read Also: Sailoz Mukherjea | Biography | Life | Artworks

|

A Woman with a Parrot

|

The two painters’ work had many points in common stylistically speaking. However, there was an open challenge between the two, both bearing the statue of the head of a school, yet very different as people.

Critics had not forgiven Manet for the scandal two years earlier, and attacked the painting, calling the head “flat and ugly” and the effect of the pink of her skin and clothes a failure.

Théophile Gautier, in particular, succinctly summed up the failures of the painting from the perspective of academic conventions: “When a painting has no composition, nor drama, nor poetry, the execution must be perfect, and this is not the case here. ”

The painting works with a refined contrast between the large pink area of the ample dress and the pearly gray of the background, which taken up again and varied in the parrot’s plumage.

The rich color a mixture of the pink, veined with gray, stands out through the break of the white cuffs, the necklace and pendant, the lilac ribbon in her hair, and the black tip of her shoe.

A third note is introduced by the yellow of the perch’s base, which is reflected in the animal’s glass of water, along with a peeled lemon, which also appeared in Astruc’s portrait of the same year.

|

| Le Fifre (The Fifer) |

Fifre and Le Fifre, the image of a little chamber boy with an imperious gaze, a model whom his friend Commandant Lejosne had found him.

Marking the beginning of a long friendship, the young Émile Zola wrote an enthusiastic review of the painting, whose char.

acter clearly had much in common with what Zola presented in his writing. “I do not believe it possible to get a more powerful effect with less straightforward means.”

Doing away with all details, Manet concentrated on the figure of the little boy depicted against a neutral background.

Its intentional two-dimensionality is accentuated by the black border that encloses every form. This stylistic quality, with its intense modernity, must have further disturbed the minds of the jury, which was dominated by classicist painters such as Cabanel and Meissonier.

Handled like a playing card illustration, creating “an amusing example of still Barbarian imagery.” As he had done before, Manet elevated a subject from a genre piece to the dignity and size of an official portrait, turning it into a modern icon.

|

|

Races at Longchamp

|

The races were held at the Bois de Boulogne outside Paris and were frequented by a young Edgar Degas, whose bourgeois background was on par with Manet’s.

Degas dedicated a series of paintings to these high society events and horses. But this work, now in Chicago, is the first painted representation of a race captured at the moment of the highest energy.

Everything seems to take place in a second; the arrival of the horses that raises a cloud of dust, the clouds that pass in the sky, the sounds of the animals and crowd.

Given the fairly small size and extremely rapid execution, it is likely that the painting was an early study for a work of a larger size, which met with the same fate as the Bullfight from which the fragment of the Dead Toreador came.

|

| The Execution of Emperor Maximilian |

The artist, who was a faithful Republican and personally experienced injustice in the continuous rejection from official exhibitions, sponsored by the Emperor.

Worked on the subject for an entire year, making four different paint. ings, drawing on several journalistic accounts.

He borrowed from Goya the lateral perspective and the protagonist’s white shirt but took away the dramatic charge of Goya’s work.

The figure of the emperor is set, flanked by two Mexican generals, calm and inexpressive, who were executed with him.

Past the wall that serves as the backdrop for the shooting, a group of onlookers is depicted in Goya’s style, watching the event with curiosity.

|

|

Portrait of Théodore Duret

|

He had met Manet by chance in 1865, in a restaurant in Madrid where Manet had verbally attacked him, taking him for one of Olympia’s detractors.

Despite that incident and the fact that Duret was not at first completely sure of the art of his fellow Frenchman, a strong friendship arose between the two, to the extent that Manet entrusted his paintings to him during the war of 1870 and made him executor of his will.

The future writer told of how, when the portrait was completed, Manet decided to add the stool to the right, painting the red cushion, carafe. glass, lemon, and light blue book fallen to the ground to add a note of color to the general gray tone, which he felt was too lifeless.

He would introduce the work as a creation of a fashionable painter and then declare its real maker, thus breaking down prejudices. Manet followed his suggestion to a degree, making his signature upside down, and therefore hard to read.

The signature is placed by the tip of the walking stick and Duret seems to be polemically indicating his friend’s identity.

Read Also: N. S. Bendre | Biography | Life | Artworks

|

| Luncheon in the Studio |

Originally the luncheon was set in Manet’s studio, which could be identified by the glass pane in the background. This was later turned into a wall. Only the arms and Orientalist ornaments explain the title, though they were not even part of Manet’s equipment.

The work represents the end of a luncheon, for which a neighbor posed, who is seen smoking intently to the right.

The still life of objects to the left, along with the plant in the large decorated vase, is a complementary pairing for the still life on the table with the remains of the meal.

The painting’s different components are unified by its fluid and powerful execution, making use, as per his habit, of tone-on-tone variations, the whites of the tablecloth, the cup of coffee in the middle ground and the figure of the maid, all worked on a scale of grays and whites.

Though the work is absolutely modern, it cannot be understood without Dutch painting and Velazquez’s work, a constant difference between Manet and the impressionists, who never drew on past models.

|

| The Balcony |

he other two figures were also artists connected to Manet. Fanny Claus, a young violinist, was a friend of his wife Suzanne, and Antoine Guillemet, a painter who was well-situated at the Salon, helped Manet get his second medal in 1881 and let Cezanne exhibit at the official exhibition in 1882.

Again taking inspiration from a Goya painting, Majas on a Balcony, Manet arranged the figures behind the green iron railing on the terrace of his studio.

Though Manet had the women wear two lightweight white dresses and added other details to soften the sharpness of the green, as well as the blue of Guillemet’s tie (such as the vase with the hydrangea, the floral bouquet in Fanny’s hair, her ochre gloves, and Berthe’s red fan) the cool, bright colors were judged overly harsh by his contemporaries, who also deplored, as usual, the lack of grace in his figures.

Berthe Morisot, intense and melancholy, wrote to her sister about her impression of the Salon, where she saw herself as “strange rather than ugly”, and added, “It seems that those looking at me have murmured the words “femme fatale.”

|

| Repose (Portrait of Berthe Morisot) |

The painting was made right after that of Eva Gonzales, the young Spanish woman who had ignited Manet’s enthusiasm (and whom he took on as his only student) and had incited Morisot’s jealousy.

Without question, Manet sincerely admired the work of the painter, an eminent impressionist who ended up marrying his younger brother, The title notwithstanding, Morisot remembered the agony of the long sessions of posing, during which she could not move her left leg, which was bent under her so as not to change the distribution of the skirt’s folds.

The figure of Berthe, wrapped in the white cloud of her dress, has an unfocused quality that makes her seem far from the present, absorbed in her thoughts, prey to those “chimera that made me unhappy” (as she wrote in a letter to her brother).

|

| Berthe Morisot with a Fan |

In this era, Berthe was the preferred subject of a vast series of portraits in oil and watercolor This small work, which hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, did not have the official aspirations of Repose, a painting made for the Salon, and its domestic intent makes it a work of exceptional spontaneity.

Manet wittily and affectionately portrays a private moment. in which “Morisot, elegantly garbed in a black dress and a pair of light-colored shoes, plays with him, bringing an open fan before her face, preventing him from making a real portrait.

This creates strong complicity between Manet and his friend, and he captures its fundamental details, letting secondary elements fall away Even in its speed, the composition is deftly structured.

whose unnaturally warm luminosity is echoed in the visible part of her legs, her shoes, and the seatback.

Berthe is sitting diagonally so that our gaze runs from her feet, which attracts the eyes with their light color, along with her whole figure, stopping to rest on her face.

With his intuition and experience, Manet successfully amplified the effect by leaving the space to her right empty.

Read Also: List of American artists before 1900

|

| The Railway |

They were celebrated by Monet in a series of works in 1876 and 1877. Five years before him, in this painting, Manet had been the first to use the station as the focus of a painting, which was accepted at the Salon of 1874.

He depicted his former favorite model, Victorine Meurent, posing ten years after Olympia, and the daughter of a friend, wearing an elegant white and blue dress.

The woman is holding a book and a sleeping dog on her lap, a copy of the one in Titian’s Venus of Urbino, which had been the source for his scandalous nude ten years before.

Returning again to the powerful theme of The Balcony, Manet portrays an iron fence whose bars mark the rhythm of the painting’s entire surface.

Here the bars separate the background from the paint- ing’s two female figures, keeping us, the ideal viewers on the same side, outside of the bars.

This extraordinarily innovative invention was predictably condemned by traditional critics with sarcastic remarks like, “These poor girls, seeing themselves painted like this, wanted to escape! But, with foresight, he put a grate to cut off any escape route.”

His friend and astute critic, Burty, understood the subtlety that informs the work, noting that “The movement, the sun, the clear sky, and reflections all give the impression of nature, but a nature captured by a delicate spirit and translated by a refined soul.”

|

| On the Beach |

He had already worked outdoors, though mainly making sketches, which he later used to work in his studio.

It was undoubtedly the influence of Claude Monet, a prominent member of the Batignolles group head. ed by Manet, and particularly close to him in the 1870s, which led him to paint completely outdoors, as evidenced by the grains of sand found on the canvas surface.

Scenes portraying figures on the beach had been a particular specialty of his chosen master, Eugene Boudin, and Monet had also painted several of them.

Their works, however, used long perspectives, capturing groups of people who were usually moving, giving an impression of wind and leisure.

On the contrary, Manet’s painting is one of great concentration. The two subjects, his wife Suzanne, intent on reading, and his brother Eugene, in the same reclined position that he had adopted ten years earlier in Le déjeuner snr l’herbe, are still and engrossed.

Most importantly, they are captured in a close foreground, with a tight perspective that crops the blue of the sky, leaving only a thin strip visible, His choice of a very low horizon, and to portray the two figures in profile, making them appear as flat triangular shapes, similar to the dark sails of the boats that mark the visual rhythm of the back’ ground’s blue, tie Manet’s painting to Japanese prints.

He had studied such prints for years, and they were elected a revolutionary mod’ el for the style of two generations of French painters.

|

|

Le Bon Bock

|

Shown at the Sa- Ion of 1873, the work replicated the 1861 success of The Guitarist. Critics and the public admired the subject handled by Manet with unusual warmth.

The figure was immediately likable, with his rosy face, abundant stomach held by his partly-buttoned vest, and the details of his outfit, such as the knotted scarf around his neck and the smoke floating from his pipe.

The more classic style and finished execution, less “patchy” than usual, made Manet’s work acceptable and even admired. For the exact same reasons, though from the opposite perspective, Manet’s young colleagues did not appreciate the painting.

They considered it a sinking of his standards, an obvious compromise with the inclinations of the jury and the academic public.

His success even became a deterrent to continuing to represent at the official exhibition, as it made it clear that the only way to get the sought-after approval was to bend to the traditional taste.

On the other hand, the work showed strong connections to the paintings of the Dutch Frans Hals, a contemporary of Rembrandt, whom Manet particularly admired and whose active, vibrant style undoubtedly influenced Le Bon Bock.

The baritone singer Faure bought the painting for 6,000 francs that same year. A few months earlier, a periodical had mistakenly announced that a collector was offering Manet 120,000 francs for his painting, which brought Manet into the editorial office.

Demanding that the journalist “name the madman who wanted to pay 120,000 francs” for his painting.

Read Also: Post-Impressionism

|

| Woman with Fans |

Esteemed composer and generous hostess, supporter, and lover of many penniless young talents, she was also neurotic and alcoholic, already dying at only thirty-nine years of age.

The wallpaper and Japanese fans that adorn the background had been in fashion in Paris for some ten years. Renoir and Monet also used similar sets in their works from the same period.

Nina wears one of the Algerian dresses that she liked to wear during her receptions, and her elegant garb contrasts with the casual pose in which the artist portrays her, reclined with an elbow propped on some cushions.

Manet looks upon his model with clear fondness, grasping her psychology as well as her worldly aspect. The woman has a gaze both absorbed and tired, with a hint of a smile that does not mask her melancholy.

In her image Manet captures the double nature of an urbane person and sensitive artist. Stylistically, Manet uses a rapid, lively touch that skims over details to convey the impression of the whole.

The smaller, more fragmented brushstrokes that are found in some areas of the painting were unquestionably influenced by the ideas of his young colleagues, while the luminous, shiny black so characteristic of Manet triumphs in Nina’s dress.

|

| Argenteuil |

self there, and his friend Renoir also visited often. Manet owned a family home near Gennevilliers and spent the summer of 1874 there, the period in which he came closest to impressionist ideas.

He had already made a few forays in that direction in previous years, and now assiduously dedicated himself to studying figures outdoors, and he may have completed entire paintings there, such as this one.

Not only are the two figures portrayed directly on the river in the midst of nature, but, significantly, the painting is informed by a strong new luminosity and a fresh, genuine air is felt for the first time.

A boatman (for whom Manet’s Dutch brother-in-law posed) and a young woman sitting on the edge of a boat. The man shows a clear interest in his companion, while she gazes expressionlessly in front of hen According to Théodore Durer, Manet had perfectly captured the spirit of these Sunday couples, whose middle-class women had insipid, lazy ways. However, the painting’s exceptional quality is in its rapid and lively execution.

Manet delicately modulates the colors, giving up strong dark and light contrasts almost entirely in favor of a continuous mixture of light and shadow.

His clean and essential marks achieve unprecedented tension in the woman’s skirt and flowers, where the colors merge and affect each other like in the works of the impressionists.

The work was exhibited at the Salon of 1875, where it was, of course, poorly received by traditional critics, who declared Manet’s “bankruptcy” after his isolated success with Le Bon Bock.

|

|

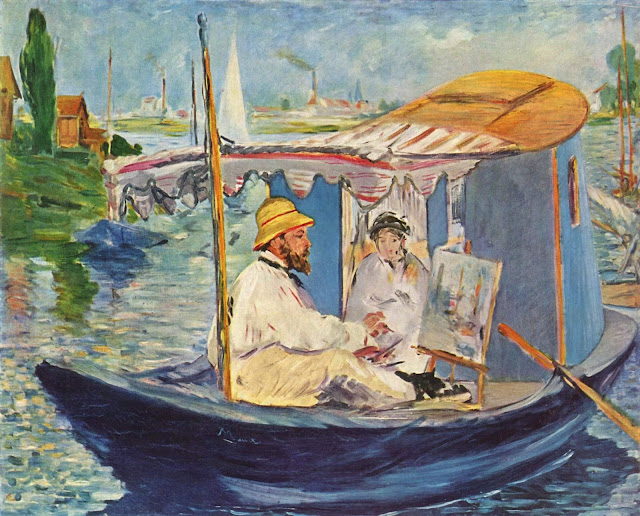

Monet Painting in His Floating Studio

|

Manet imposed long sitting sessions on his models. He likely did not wish to subject his friend and his young wife to such a procedure. complicated by the subject itself.

The idea of a floating studio was not Monet’s. He had taken it from Daubigny, an eminent Barbizon landscape painter and friend and supporter of Monet’s, who experimented with the idea, which became well-known for its originality in the 1860s.

The painting’s true focus is the boat itself, which covers almost the entire length of the surface. Monet is portrayed in profile, intent on working on painting still in a draft state.

His wife Camille is cloaked in a white dress, contrasting with a black hat, and watches him paint at a respectful distance.

The shore of the Seine can be seen beyond the boat. where the green of the countryside merges in the distance with the factories of the Parisian outskirts.

The light-colored, luminous painting (despite the black swath of the hull) is dominated by the blue tones of the sky, the boat’s cabin and, especially, the water. The rendering of the water is what brings Manet’s painting closest to those of his colleague.

Manet uses a dynamic, vibrant hand, boldly stippling the water with yellow, green, pink, and black with the same process of colored shadows and mutual reflections that Mon- et was busily applying to his works in this period.

|

| Madame Manet on a Blue Sofa |

Much in vogue throughout Europe in the nineteenth century, pastel had been gradually abandoned, and the artists of the Batignolles group rediscovered it.

It is unclear who deserves credit for getting there first, but the contest is certainly. tween Manet and Degas, who experimented at length with its expressive potentials in the Dancers and Woman at Her Toilette series.

This work depicts Suzanne reclined on a couch, captured in a moment of rest before or after a walk, as indicated by her jacket, elegant shoes, and her hat with the undone tie.

The subject was often taken on by Renoir and Monet, who painted Monet’s wife, Camille, stretched on a divan several times in the same period.

There is no need to theorize direct influences, as the painters’ discussions would have naturally led them to work on the same subjects.

Manet took advantage of the velvety effect of pastel, which oil paint lacks, though he again made an image firmly anchored in painting tenets, as seen in the large contrasting color surfaces, as well as the effect of the sofa’s slightly mussed fringe.

The work was bought by Degas, who kept it in his studio for the rest of his life. When his collection was sold, the Louvre bought it for 62,000 francs.

|

|

Portrait of Marcellin Desboutin

|

It is unknown where the two artists met, though most likely it was at Café Guerbois, which Desboutin started to frequent around 1870, or at the Café de la Nouvelle Athénes, the new headquarters of the Batignolles group since 1872.

Manet considered the etcher “the most extraordinary fellow in the neighborhood” for his composure and serious dignity; he was also Degas’s model for The Absinthe Drinker.

Manet portrayed him standing with a neutral background like he had used in many previous portraits. He abandons the ranges of gray in favor of brown tones and a warm luminosity.

The dog, though with distant echoes of those depicted by Velåzquez and Jacopo Bassano, is painted in a new style, with a dynamic touch and a chiaroscuro effect that fills the animal’s figure as he is intent on drinking from a glass.

Manet intended to place himself as an heir to the great painters of the past, equaling their creations in modern interpretations. For Desboutin’s portrait he used a freer execution and more exuberant brush strokes than bef6re, which did not win the favor of the jury of the Salon of 1876, who rejected his painting with thirteen negative votes out of fifteen total.

The academic world was dismayed by the success of Le Bon Bock, and especially by the semblance of legitimacy thereby created for a painter who was at the same time identified as the leader of impressionism.

Discouraged and furious, Manet organized an individual counter-exhibition in his own studio, visited by a large crowd. The invitations came with the slogan, “Make it true and let others talk.”

The realist critic Castagnary took him up on that and declared that he now holds a place in contemporary art on par with those of the most eminent artists on the jury.

Read Also: What is modern art | What is “modernism?

|

|

Portrait of Marcellin Desboutin

|

First he was friends with Baudelaire and Zola; in 1873 he met the young poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who, as the others had, quickly picked up his pen to defend and praise Manet, whom he considered “the only man who has tried to open a new path in painting”, as he wrote in the article “The Painting Jury of 1874 and Manet,” published less than a year after they met.

An intensely personal and professional understanding was born between the two at the instigation of Mallarmé, ten years Manet’s junior. Manet made illustrations for several of the poet’s works and translations.

The extraordinary natural quality of Manet’s portrait of him makes it one of the highest and most modern achievements of his career The small painting has extraordinary expressive power and charisma.

The writer is captured in a quotidian moment in Manet’s studio near Gare Saint-Lazare, which can be recognized by the wallpaper also found in Woman with Fans.

Far from the official quality (even pomposity) of the Astruc portrait, Mallarmé is depicted with a hand in his pocket and his back resting on a cushion arranged against the wall.

His other hand holds his beloved cigar and seems to indicate a point on a page as if he were marking his place during a conversation or a pause for thought.

Here Manet gives up on his notorious, strenuous posing sessions, allowing him to achieve an effect of great immediacy.

The economy of the rapid brushstrokes and the engrossed poet’s crooked position convey a communicative intensity uncommon in the generally cool atmosphere that Manet favored.

|

| Skating |

The words of the great poet seem to form the backdrop of the painting. He asked artists to portray “the transitory, the fleeting, the contingent,” and Manet recorded this very aspect of modernity.

Staying true to the dictates of his dead friend, which were the same as his (both were absolute “men of the world”), Manet made “a sketch of customs, a representation of bourgeois life and fashionable shows. ”

The woman in the foreground is Henriette Hauser, a young actress quite well-known in the milieu of the boulevards for being the lover of the Prince of Orange.

Manet had met her in Nina de Callias’s house, and she had already posed deshahilé for Nami. The woman has a distracted, smiling expression, though without the coquettish air she had in Nanci, also inspired by Zola’s novel.

She wears an elegant embroidered jacket, which appears to be a lightweight skirt, and the ever-present pair of gloves, a constant attribute of refined figures.

Manet paid special attention to reproducing her elaborate outfit, which becomes the focus at least as much as Henriette herself.

With a masterful hand—dynamic and lively—Manet perfectly conveys the lightweight atmosphere of the evening, filling the surface with an amorphous, noisy crowd and creating a moving, animated image, very different than the static quality of Music in ‘he Tuileries Gardens from 1862.

Though his brushstrokes show the undeniable influence of his impressionist friends, he stays true to himself. orchestrating a proper “symphony in black”.

|

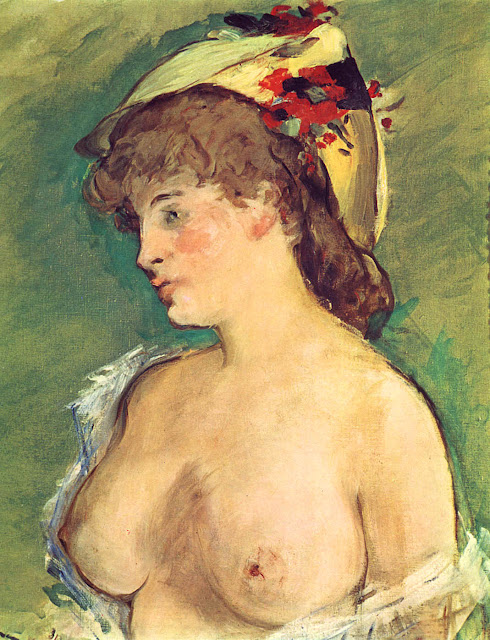

| Blonde with Bare Breasts |

Manet’s work seems, in fact, to be a kind of challenge to his colleague, as critics, commenting derisively on the purple and blue reflections in the skin of one of his figures, suggested that the artist had found his models at the bottom of a canal.

Manet did not go so far as to paint the reflections of the surrounding environment on the woman’s skin. Instead, he shapes it by turning his brush with a sure and rapid hand, marking the form’s edges with a dark line.

Contrasting with the finished, polished look of the woman’s body, the dress has an irregular look, the hairstyle is tousled, and the yellow hat, quickly sketched, adorned with a few red flowers.

The background is disorderly and covered with a bright green color which serves as a visual buffer, bringing the female figure, and her serious, thoughtful face, towards the viewer.

Manet’s wife, Suzanne, sold the painting to the dealer Ambroise Vol- lard (a pioneer supporter of modern painting) in 1894 for 500 francs, a price that seems quite low for the time.

It was later bought by Moreau-Nélaton, a leading Manet collector and scholar, who donated it to the Louvre in 1927.

Read Also: World’s ten most expensive paintings

|

| The Waitress |

Manet employs a mode of composition that recurs in his paintings from this period, which takes the viewer’s gaze into consideration.

Manet again uses, to a much greater extent, the device of having the people and objects cut by the natural end of the canvas. Here the method is used for all four sides of the painting.

The figure of the person in the foreground, the beer mugs on the right, the lights on the upper edge, and the body of the dancer to the left are all only half depicted so that the viewer has the impression of participating in the scene.

The surface is also cut in two vertically. The left side has a reddish background, marked diagonally, in front of which the spectators’ top hats rise; the right area shows a wall with a light-colored wallpaper decorated with flower bunches, in front of which the waitress turns and looks at us.

Stylistically speaking, the work expresses strong similarities with impressionism, though Manet sticks with his more contrasted palette and, significantly, chooses not to adopt a uniform kind of execution.

For the left half of the painting, as for the foreground figure, he uses a broken, often diagonal brushstroke. The face of the man intent on smoking the pipe fully adheres to the studies of his younger colleagues.

The figure’s skin and hair are broken down into several hues, and Manet makes the use of colored shadows. The waitress’s face and the collar of her dress are made with a more traditional technique, painted with patches of color.

|

| In the Conservatory |

Manet took the idea of the railing from The Balcony, and doubled it, though with a weaker impact than in the painting from ten years earlier. Space is quite carefully constructed.

The geometric weight of the bench is countered by the proliferation of plants in the background. These plants alternate with the figures and set a pace for space’s horizontal view.

Their green mass, though handled like wallpaper, gives particularly vibrant emphasis to the yellow of the accessories worn by Madame Guillemet, renowned for her beauty and good taste.

The couple’s apparent distance is contradicted by the closeness of their hands, introducing an intimate atmosphere.

Conservatories were a fashionable setting during the Second Empire. Zola turned them into places of clandestine romantic encounters in his 1872 novel, La Curée, and succeeded in raising a scandal.

Manet exhibited the painting at the Salon of 1879, where the association with Zola was advanced by some malevolent critics, despite its lack of ambiguity.

The painting was exhibited together with In the Boat, set- ting an intentional contrast between the social status of the two couples.

Manet had managed to obtain a meeting with the assistant secretary of state, suggesting the public purchase of one of the two paintings or the admired Le Bon Bock, in order to be represented in Luxembourg in the Museum of Contemporary Art.

The offer was ignored and the state never bought any works by Manet during his life.

Attesting to the work’s vitality and it’s evoking of an era, however, in the recent film based on the Oscar Wilde novel The Ideal Husband, this painting is explicitly quoted in one of the final scenes.

|

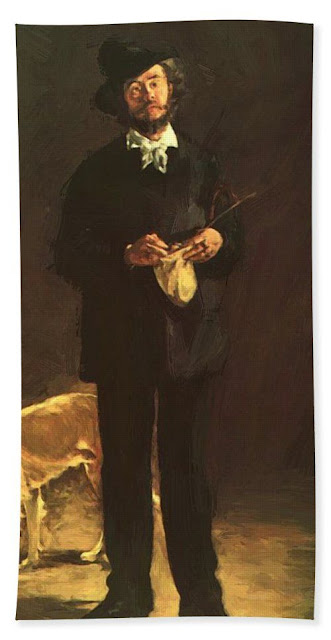

| Self-Portrait |

His hair and beard are light browns; his eyes are narrow and deep and have a youthful liveliness and fire… His face has a fine and intelligent irregularity, which as a whole professes agility and daring, disdain for stupidity and banality.

If we move from the face to the man, we find in Édouard Manet a person who is exquisitely amiable and courteous, with distinguished ways and a likable appearance.

” At the time of this self-portrait Manet was forty-seven years old, but his features still convey the characteristics evoked in his friend’s analysis. He portrays himself with a brush and palette in hand, though wearing his jacket and hat, which he is unlikely to have worn while painting.

This is a constructed presentation, in which Manet depicts himself as a dandy, according to Baudelaire’s precept, though the pose is also reminiscent of the mirrored pose in Las Meninas (Madrid, Pra- do) by Velåzquez, Manet’s favorite artist, of whom he aspired to be a modern equivalent.

Manet drew on one of his oft-used color combinations to paint himself: a neutral background of a brown hue against which the ochre of the jacket stands out, taken back up in the brushes and palette, almost is if the artist wished to say that his realization as a man moved entirely through his work.

|

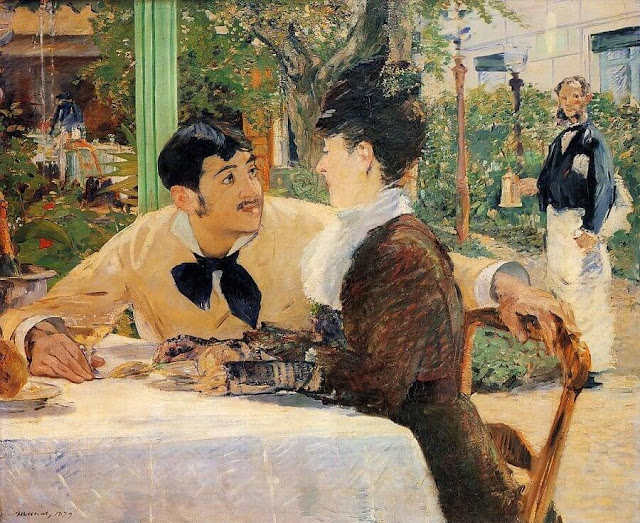

| At Pére Lathuille’s |

The painting, which has fresh and spontaneous air, does not immortalize two strangers, but rather a couple constituted by posing the son of the café owner with the actress Ellen André, a friend of Manet’s.

André’s acting commitments forced Manet to replace the model, and he also decided to change the young man’s clothing, who was originally painted in a dragoon uniform.

In contrast to the usual coldness of Manet’s characters, he gives a close, amusing description of the psychology of the improvised couple.

The woman is visibly older than her companion, and has a composed and rather a rigid posture, with her back, held away from the seat, her mouth tight and her gaze lowered.

The young man, who seems to have grown his mustache and sideburns to look older than his age, is relaxed and outgoing.

Bending towards his companion, with this eyes fixed on her face, he familiarly stretches an arm on the backrest of her chair, while his other hand distractedly grips a glass whose contents echo the yellow of his jacket.

Manet also chose the colors to emphasize the distance between the reserved reticence of the woman dressed in dark clothes and the warm, expansive attitude of the young man, with bright clothing, tempered by the black scarf knotted around his neck.

Manet’s spirited brushstrokes portray a wide view of the cheerful restaurant with its decked out tables in an internal garden.

On the right, behind the young man’s hand, he painted a waiter who stops to watch the scene of courtship, perhaps ironically mirroring our voyeuristic attention as spectators magnetically were drawn to the couple.

|

| The Asparagus |

The piece had been bought for 800 francs by his friend, an art historian, and banker, Charles Ephrussi, who had instead sent 1,000 francs to Manet. Manet, who was equally the gentleman, chose to thank him as best he knew how by giving him another painting.

He made the painting and sent it to Ephrussi with a note: “One was missing from your bunch.” Unlike the first work, which was conventional and structured, The Asparagus presents extraordinarily expressive and compositional freedom. The tiny piece of produce is placed on a marble top that runs slightly diagonally to the painting surface.

The table runs vertically up the entire available space, free of any other indication of place or time.

The color combination also evinces great sophistication. Manet chooses an elegant tone-on-tone variation, echoing the asparagus’s ivory hue in the table material, and repeating purple, pink, and green tones in the veins of the asparagus’s tip.

Though the painting originated in a particular circumstance, it is related to a small group of similar pieces from the same period, often made as small gifts, such as the aforementioned bouquet of violets for Berthe Morisot, and three apples painted for another friend, Méry Laurent. Similar themes, mostly in watercolor, are also found in Manet’s letters accompanying his writing.

|

| The Escape of Henri Rochefort |

After the fall of the Commune, he was imprisoned and deported to New Caledonia in 1873, from where he made a daring escape the following year.

He returned to Paris in 1880, with amnesty, turning, however, into an ardent anti-Semite. Manet, who admired the radical Republican in him, undoubtedly met him in 1880, at the latest, through their friend Desboutin.

Manet romanticized the event to charge it with extra drama and heroism. The escape was not actually in the open sea but in a commercial port of the island where they were kept, prisoners.

Manet intended to present it to the Salon, returning to the idea of a historic sea scene, as he had done with The Battle between the Kearsarge and Alabama, though now radicalizing the composition.

|

|

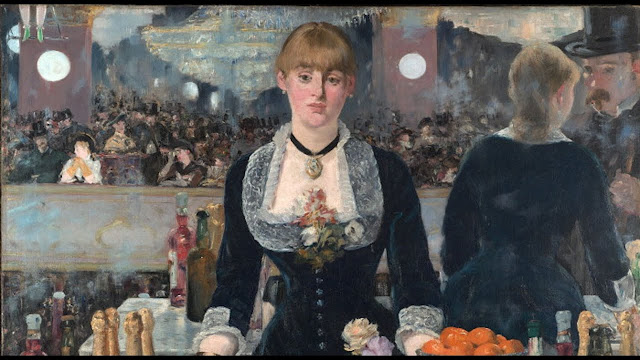

A Bar at the Folies-Bergére

|

The painting contains many of the characteristic components of his entire career: the Parisian setting, the slice of modern life, its calibrated composition, and the use of black and extraordinary still life.

However, the piece has a psychological subtlety rarely achieved by the artist, along with a very balanced execution, touched with impressionist echoes interpreted in a personal manner.

Manet once again plays with the effect of placing the viewer within the painted space, though here he weaves a particularly subtle dialogue between the observer and the observed.

At first glance, it gives the impression of a conventional scene in which the barmaid, absorbed and melancholy, looks at us without seeing us, and behind whom we have a wide view of the customers at the crowded bar.

A closer look reveals the detail to the right, making us aware that everything we see behind the girl is actually a mirror reflection.

The spatial relationship is unexpectedly complicated and the customer in the top hat to whom the barmaid turns without seeing him coincides with the viewer.

As in the masterpiece by the much-venerated Velazquez, Las Meninas, the reality is not as it appears.

The attitude that seems solicitous. when looking at the girl from the back is not actually there. The Folies Bergere, a concert café in vogue at the time in Paris, has frequented by all sorts.

This gathering place par excellence is here turned into a place of absence and loneliness.