Among other interesting facts, their planning, and treatment generally throw considerable light on the system which prevailed in these retreats, and reveal the manner in which the practical requirements of the community were provided for.

In their broad aspect they also demonstrate that the Buddhist monachism of India had much in common with the monastic establishments of Europe, a condition due to the similarity in their aims.

For instance, the Buddhist monks, as did their Cistercian brethren, planted the houses of their order in wild and desolate places, for apparently the same reasons that they might conduct their observances undisturbed by the distractions of any human environment.

Then, in connection with the former were developed the “carralls” or small study-rooms, whereas in the latter these took the form of cells leading out of the central court.

In the course of time the full complement of each type of monastery, whether European or Buddhist, was composed of a dormitory, a common room, a refectory or frater, a kitchen with other service amenities, and, in the case of the former a fish pond, and the latter a tank for the water supply.

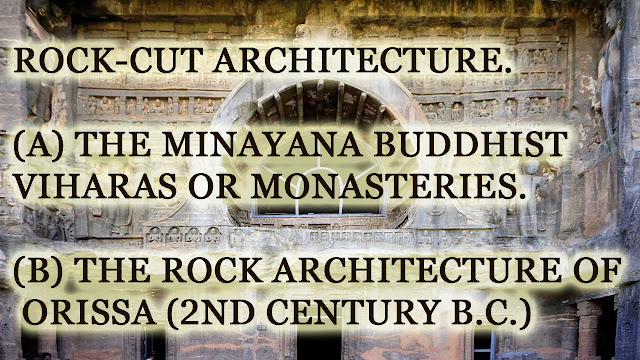

All these rock-cut viharas were by no means alike in their design, they took a variety of forms, but a representative example of the earlier or Hinayana type may be distinguished from that of the later or Mahayana, by several well-defined characteristics.

Chief among their typical features was the open simplicity of the central hall, for, with one or two exceptions, this assembly room was a large square compartment, its space uninterrupted by any formation of pillars or colonnade.

Owing to the situation of the couch in such small cells, which average only nine feet square, the doorway is not in the center but to one side of the outer wall.

In these rock-cut copies of the structural original it is quite easy to see that the central hall corresponded to the open courtyard, while the facade, vestibule, and cells were all translations, in the rock medium, of the conventional wooden type of viharas, of which, owing to their impermanency, no examples have survived.

This first series consisted of five excavations in all, two of which, Nos. 9 and 10, are chaitya halls, while there are three viharas, Nos. 8, 12 and 13. It will be noted that No.

11 is omitted from the series as it is a Mahayana vihara rather awkwardly interposed at a much later date.

Chaitya hall No. 10, with its attached vihara No. 12, were the first to be cut, vihara No. 13 being added shortly afterwards to accommodate the increasing body of monks.

Then, most probably because the priestly community had been still further augmented to justify the production of another house of prayer, chaitya hall No.

9 was excavated, together with vihara No. 8 as its accompanying monastery. Of these early viharas, No. 12 provides a simple but typical example of the single-storied variety, although its facade has almost entirely disappeared.

Around its square central hall is carved that horse-shoe arcading characteristic of the work of this phase, its upper portion resolving itself into a pleasing frieze.

Every feature is planned and cut with remarkable precision, the facility with which the artificers chiseled out the surfaces and finished off the ornamentation being noteworthy.

The exterior, although much of its lower part has broken away, is a very interesting production, as originally it consisted of a pillared portico, the end walls of which still remain.

Projecting over this portico is a massive cornice, together with a feature corresponding to an entablature, every detail of which is an exact copy of intricate wooden construction.

Within the portico is a screen wall with three square-headed openings, forming the doorway and a window on each side.

Inside is a large hall measuring 23 feet by 29 feet, surrounded by a colonnade, and with cells opening out from the three interior sides.

An instructive motif carved on the end wall of the portico is a conventional representation of a chaitya hall facade, from which it is possible to gain no little information as to the final appearance of these frontages.

The other Hinayana monastery with pillars in its central hall is that at Pitalkhora, but of this example all that remains are a few of the cells.

These cells, however, are not plain square rooms as in all the other viharas, but small vaulted chambers with ribbed roofs and lattice windows, reproductions in miniature of the work of the carpenter.

The exteriors are as ornate as the interiors, as between the overarch of each doorway is a Persepolitanpilaster surmounted by addorsed animals or gryphons.

|

| Buddhist Vihara |

Judging by the style of their design and workmanship, supported by inscriptional evidence, they appear to have been executed in the first century A.D. According to their inscriptions they have also been named, Gautamiputra(No. 3), Nahapana (No. 8), and Sri Yajna (No. 15), Nahapanahaving been the first to be excavated, followed shortly afterwards by the two others.

All have columned porticos and large central halls without pillars, out of which open the usual range of cells containing in most instances stone beds.

The series of four, with a half pillar at each end, which form the Nahapana facade, are almost exact copies of those in the interior of the Ganesh Lena chaitya hall at Junnar, both of which in their turn having been derived from the portico pillars at Bedsa, every detail, from the lotus-base on the stepped pedestal below to the animal groups on the abacus above, being the same.

Under its enormous weight these stalwart atlantes, rising out of the earth, with bulging muscles stagger along, seeming to represent elemental beings from an underworld, forced into the service of the creed.

In some respects, the treatment of this doorway recalls that of the Sanchi toranas, as it has lintels or crossbars with voluted ends, but like most of the rock-carving at Nasik, although it retains the principles of the style, shows a marked originality and independence in certain details.

Then, several centuries afterwards, when the Mahayana priests took over these early monasteries, the interior of this particular vihara appears to have been considerably altered in order to make it suitable for the performance of the later theistic ritual.

Such a procedure presented no special difficulties, as the floor was merely sunk so as to provide a square dais towards the middle of the central half, and a cella excavated at the far end with a pillared antechamber for the accommodation of a large image of the Buddha; the style of this alteration indicates that the seventh century was the date of its conversion.

This resolves itself into a collection of chambers, not Buddhistic, but attributed to the opposing belief of the Jains, as in their treatment there are certain features implying a connexon with the latter creed.

Nor are there any chaitya-halls, for they consist in most instances of a formation of cellular retreats recalling in some respects the viharas of the western Hinayana type.

The close grouping on two low hills, not far removed from the famous Brahmanical fanes of Bhubaneshwar, supplies additional proof, if such were required, that this area was of special sanctity, the whole country around having sacred and historical associations.

As a token of the antiquity of these parts, near at hand is Dhaulihill, where is inscribed one of the rock edicts of Asoka, guarded by a fine sculpturesque representation of an elephant.

The two tree-clad hills in which the rock-cut chambers are situated, are, together, locally known as Khandragiri, but the northern elevation is called Udaigiri, Separated by a defile, between them wound the “Pilgrims Sacred Way,” or Via Sacra, to Bhubaneshwar, where it is likely there stood, in early days, a stupa—the pilgrims’ goal.