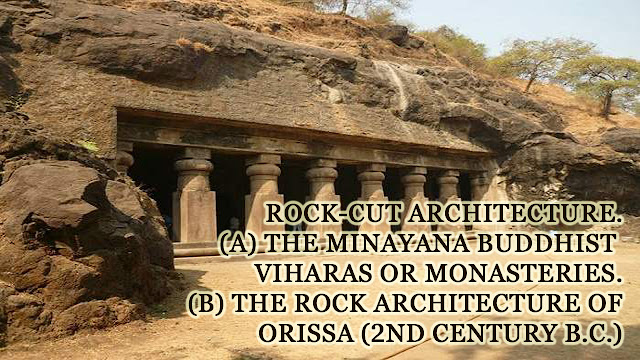

ROCK-CUT ARCHITECTURE.(A) THE MINAYANA BUDDHIST VIHARAS OR MONASTERIES. (B) THE ROCK ARCHITECTURE OF ORISSA (2nd Century B.C.)

This inscription records, among other information, the chief episodes in the reign of king Kharavela, ruler of Kalinga, the ancient Orissa, including his conquests of a great portion of the north and cast of India.

Kharavelawas by religion a Jain, and appears to have been personally interested in the priestly community who had selected these hills as a place of retreat.

ft is just possible that the small group of Ajivika hermits responsible for the excavated chapels in the Barabar hills, having lost the protection of Asoka on the death of that monarch, migrated to Orissa, not only to be under a Jaina ruler, but in order to continue their system of living in cells cut in the rack.

In its general character this group seems to imply an independent development, having but little in common with any other rock architecture of the country.

Yet there are certain fundamental forms, both architectural and decorative, found in all this excavated work, which indicate that whether Buddhist or Jain, or whatever the locality, it was all part of the same movement, originating from one source, the beginnings of which had been introduced into the country by Asoka a century before.

As the country around consists mainly of a laterite formation, the selection of this sandstone outcrop, on account of its more workable character, is understood.

There are in all some thirty-five excavations, large and small, but only half of them are of any significance, some sixteen of which are in the Udaigiri hill, while there is only one of any importance on Khandragiri.

Apparently laid out on no regular plan, they were evidently cut in convenient places and connected by paths, still traceable through the glades of trees.

Two of these retreats consist of single cells only, three or four combine several cells having a portico with the remains of a courtyard in front, while the four largest and most elaborate are composed of galleries of chambers in double stories and overlooking a quadrangle.

None of the courtyards is covered in, as are most of those in other parts of India, but the fact that they are open to the sky may be due to the shallow configuration of the rock in which they are cut.

Compared with the Ashokan examples, or those in the Western Ghats, the workmanship on the Orissan monasteries is clumsy and crude, but such conditions may be partly accounted for by the rough texture of the sandstone.

Moreover, it seems to have little or no connexon with the remarkably fine phase of structural architecture and plastic art which developed in its vicinity at Bhubaneshwar and elsewhere under Brahmin patronage some centuries later.

The local generic name for these Orissan monasteries is “gumpha”, meaning a cave, and each is distinguished by a picturesque or appropriate prefix, as for instance the Ganesh (or Elephant) Gumpha, so-called on account of two sculptured elephants forming a prominent part of the conception.

In the treatment of the former most of the pillars have simple square shafts with bracket capitals, some of the bracket forms being of a very special character.

For instance, in one example, that known as the Rani Gumpha, or Queen’s Cave, the largest and most important of the entire series, there is a bracket of a very primitive order, not unlike the curved branch of a tree.

On the other hand, in the Manchipuri Gumpha the portico pillars support intricately carved struts made up of figures riding hippogryphs and other compositions of a similarly fanciful nature.

It may be noted that this form of bracket is the prototype of those which are a prominent feature of the Brahminical rock-cut temples at Badami in Dharwar, produced at least six centuries later.

As already observed a distinctive element in all the early rock-cut viharas is the arcading which decorates the walls, and which in the Orissan examples is of an exclusive kind.

Instead of being of the horse-shoe variety, the arches of the arcades are almost invariably semi-circular, and their lower ends, corresponding to the “springer” of a true arch, are expanded to enable them to be supported on pilasters.

These pilasters have capitals formed of pairs of recumbent animals, a decadent derivative of the Persepolitan type, and a number of them have vase bases. Another feature in some of the Orissan viharas is a ledge or podium carved like a continuous bench around certain of the compartments.

Here is seen an early appearance of the asana, a stone scat with a sloping backrest, which in a more developed and highly decorated form became prominent in the temples of Central and Western India of the early medieval period.

The cells comprising the interiors are not square as in most of the other viharas, but oblong in plan, and some are long chambers entered by several doors, in shape more like dormitories than single rooms; in place of the stone bed, differentiating the early type of cell, the floor in each compartment is sloped so as to form a couch, and as in many instances the height of the room is only four feet, they can only have been intended for sleeping.

Carved out of a shoulder of rock projecting from the hillside, the exterior is shaped like the mask of a tiger, the antechamber simulating the gaping mouth, and the cell door within this, the gullet.

On the door-jambs, which slope inwards, are pilasters with winged creatures as capitals, and pots for bases. The interior consists of a room only 3 ½ feet high, but some six feet deep and nearly eight feet wide.

Over the doorway is an inscription in characters anterior to the Christian era, stating that it was the abode of an anchorite named Sabhuti, who, reclining in this narrow cell resembling a tiger’s maw, seems to have passed his life literally in the jaws of death.

|

| Bagh Gumpha |

This “abbey church” is a double storied production with its cells ranged around three sides of an open courtyard, the fourth side comprising the frontal approach.

A broad terrace, projected from the upper story, was originally supported on structural pillars, cither of wood or stone, and these formed the verandah of the ground floor.

|

| Rani Gumpha |

A stairway cut in the rock at the side gave access to this upper terrace, on one face of which there is a spacious throne, with arms and a footrest, evidently the seat of honor of the abbot or other high dignitary.

While the general arrangements of the cells indicate that most of them were for the accommodation of the monks, there are several supplementary chambers and recesses evidently devised for special purposes connected with the ritual, cither as robing rooms or for the preparation of offerings.

In addition, there are rooms for storing the sacred vessels and vestments, with a place for the custodian or sacristan.

|

| Rani Gumpha |

For around the walls of the upper story there is a long frieze consisting of figures engaged in a series of connected episodes of a distinctly dramatic character.

As these same scenes are repeated in part, in one or more of the other viharas on this site, they evidently represent some vivid epic in the heroic age of the people.

It may be inferred therefore that this arrangement of courtyard and terraces forming the Rani Gumpha constituted an open air theatre in which the scenes depicted in the sculptured frieze around it were brought to life by being performed on festival occasions as a kind of Passion Play, in the same way that the so-called Devil Dances are celebrated in the monastery (gumpha) quadrangles of Tibet.

If so, the peculiar formation of the gumpha is at once explained, and its various parts fall into their proper place.

Moreover, it is not difficult to picture the courtyard occupied by the actors in this drama, while seated on the terraces, like an amphitheater, with the high priest enthroned in the central position, would be a closely grouped background of spectators, the whole forming a brilliant and moving pageant amidst the dark encircling groves.

1. Dadaism 2. Fauvism 3. Synthetic Cubism 4. What is Art 5. Minimalism 6. Philosophy of Art 7. Banksy’s painting 8. Graffiti 9. Facts about Paul Gauguin 10. Beginning of civilization 11.Famous Quotes by Pablo Picasso 12. Leonardo da Vinci quotes 13.George Keyt 14. Gulam Mohammad Sheikh 15. female influential Artist 16. Why did Van Gogh cut off his ear 17. The Starry Night 1889 18. most expensive paintings 19. The Stone Breakers 20. Vocabulary of Visual Art 21. Contemporary art 22. What is Digital Art 23. Art of Indus Valley Civilization 24. Essential tools and materials for painting 25. Indus Valley 26. PostImpressionism 27. Mesopotamian civilizations28. Greek architecture 29. Landscape Artists 30. THE LAST SUPPER 31. Impressionism 32. Prehistoric Rock Art of Africa 33. Hand Painted Wine Glasses 34. George Keyt

1.Proto- Renaissance: History and characteristics 2. HighRenaissance 3. KineticArt 4. Purism 5. Orphism 6. Futurism 7. Impressionism: A Revolutionary Art Movement 8. Post Impressionism 9 Fauvism | Influence on Fauvism 10. Cubism | Cezannian Cubism | Analytical Cubism | Synthetic Cubism 11. Romanticism 12. Rococo: Art, Architecture, and Sculpture 13. Baroque art and architecture 14. Mannerism 15. Dadaism: Meaning, Definition, History, and artists 16. Realism: Art and Literature 17. DADAISM OUTSIDE ZURICH 18. BAPTISM OF SURREALISM 19. OPART 20. MINIMALISM