Kinetic Art | Meaning | Definition | History

From the earliest times, artists have been concerned with depicting movement, the movement of men and animals: galloping horses, athletes running, lions leaping on their prey, birds in flight.

In other words, they have been concerned with the representation of movement, or, to be more accurate, of moving objects.

But the kinetic artist is not concerned with representing movement: he is concerned with the movement itself, with movement as an integral part of the work.

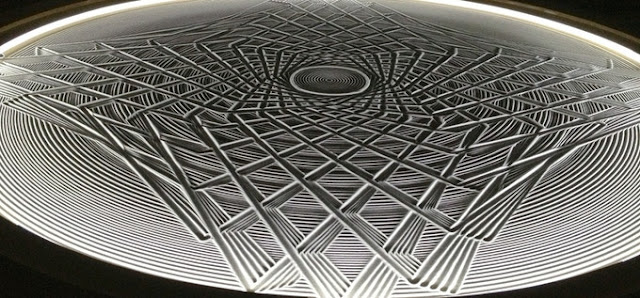

Not all works which move are considered ‘Kinetic’ nor do all ‘Kinetic’ works move. In the precise sense in which the term is used, a work of Kinetic Art must have other specific qualities besides that of moving: the movement must produce a particular kind of effect that will be discussed in a moment.

On the other hand, it is not essential that the work itself should move. The effects proper to Kinetic Art can be produced by the spectator moving in front of the work or by the spectator handling and manipulating the work.

It may even be the case, as in Op Art, that neither the work nor the spectator moves, and yet the effect may still be kinetic. But this is controversial, and I shall discuss it in its proper place.

Thus, in Kinetic Art some actual movement occurs; in Op Art, the work itself appears to move; in representations of moving objects only the object represented appears to be moving.

The only difference between, say, a sporting print and Balla’s Dog on a Leash or Boccioni’s The dynamism of a Cyclist is that the sporting print captures a momentary phase-in the movement of a horse, whereas Balla and Boccioni present you with a number of phases as they might appear if superimposed on a single photographic plate.

Instead of representing a moving object, they represented an object as it would appear to a moving observer: a street as seen from a low-flying aircraft or from a fast-moving car.

In this, the Futurists were merely developing an idea which was latent in the work of Cezanne and explicit in Cubism, namely, that of representing an object as it appears when viewed from the points of view of an observer who walks around it and not from the point of view of a fixed observer.

But this is still only a representation of movement. Movement itself does not enter directly into the composition of the work. It is not Kinetic Art in a technical sense.

Though a number of artists — Tatlin, Rodchenko, Gabo and Pevsner — were working towards the idea simultaneously, its clearest and most forceful expression is to be found in the Realistic Manifesto published by Gabo and Pevsner in August 1920.

In the course of the manifesto, they criticized Futurism (which had aroused considerable interest in Russia) for the shortcomings already mentioned: ‘It is obvious to everyone that a simple graphic record of a series of mornentary shots of an arrested movement does not re-create the movement itself.’

Then, in a language not unlike that of the futurist manifestos, they denounced the art of the past and proclaimed a new, dynamic art, the art of ‘kinetic rhythms’.

‘We renounce the thousand-year- old Egyptian error in the art which considered static rhythms the only elements in pictorial art. We affirm a new element in pictorial art, kinetic rhythms, as the basic forms of our feeling for real-time.’

By the time I mean movement, rhythm: the actual movement as well as the illusory one which is perceived through the flow of lines and shapes in the sculpture or the painting. In my opinion, rhythm in a work of art is as important as space and structure and image.

They did not intend to substitute for traditional sculpture some sort of mechanical ballet.

They did not renounce the essential and distinguishing feature of sculpture: construction in space.

But sculptors had not yet realized or taken advantage of Chis. ‘You sculptors of all shades and tendencies still adhere to the age-old prejudice that volume cannot be separated from mass. But we can take, for example, four flat surfaces and from them construct exactly the same volume as out of four tons of mass.’

The result, however, is static, although a suggestion of movement may be conveyed optically by the torsion of the surfaces and the tension of the wires.

George Rickey has aptly described these kinds of construction as ‘static celebrations of kinetic events ‘. Another way of producing the same effect is by movement.

The moving string outlines a certain area of space that creates a form or image in space and thus takes on the essential features of sculpture.

This is, as it were a paradigm, an archetype of Kinetic Art. The mobile work of Kinetic Art creates a form in space by movement.

It is not essential that the form should appear solid: it is enough that the moving object outlines and defines a certain area of space and that some form or image should emerge as a result of movement.

It is slender and translucent like some frail, ethereal vase. Gabo hoped to progress from this humble beginning to more complex kinetic forms, but he was dissatisfied with the somewhat cumbersome electric motor as a source of power.

In 1922 he made a drawing, Design for a Kinetic Construction, which was never realized. And, thereafter, for want of the technical means of, executing his projects, turned instead to static constructions.

Though Gabo does not seem to have adverted to the fact, light played an important part in producing the sculptural effect of his Kinetic Construction.

It was the reflection of light from the metal surface which created the impression of solidity. Moholy-Nagy was fully aware of the importance of light in kinetic construction.

Light not only plays on the metal parts of his machine; it also adds a new ‘sculptural ‘ element to it.

Just as the moving parts outline and define certain areas of space, so the light sweeps out and embraces the space surrounding the machine: it encompasses the environment.

This idea of the ‘sculptural’ use of light and of an ‘ environmental ‘ art was one of the most fruitful in the whole field of Kinetic Art and is the one which is being most vigorously exploited today.

Before a work of Kinetic Art, the spectator is no longer a passive or receptive observer: he becomes an active partner ‘with forces which develop of their own accord In Kinetic Art the composition is not given all at once. The spectator has, as it were, to assemble and construct it for himself.

But Moholy-Nagy regarded his works as merely experimental and demonstrative devices. He foresaw a time when the spectator would participate in the formation of the work itself.

In this too Moholy-Nagy anticipated some of the more recent developments — spectator participation.

Calder solved the problem of motive power in a way which was at once simple, elegant, and obvious: he used the movement of the air. He thus had no need to hide his source of power or try to make it an integral part of the work.

In the early thirties, he began to make what he called ‘mobiles ‘. These, in their fully developed form, consisted of flat metal plates, painted black and white or in the primary colours, red, yellow, and blue.

When set in motion by a current of air they revolve gently at varying speeds and set up a sort of counterpoint of movement. But though Calder’s ‘mobiles’ are in accordance with Gabo’s conception of kinetic sculpture, Gabo’s ideas do not seem to have had a direct influence on him.

Calder came to Kinetic Art by way of toy-making. His use of primary colors may be traced to Mondrian and the forms which the metal plates take — and indeed the playful spirit of the ‘mobiles’ — to Miro.

It seems to lack seriousness; its proper place, some people would think, is the toyshop. But since the Second world war, and particularly since the fifties Art has increasingly engaged the attention of serious artists.

But it would be futile to attempt to summarize all that has been done in twenty years. I shall, therefore, consider only the in which artists have worked, and, for convenience. group their works under four heads:

1. Works involving actual movement.

2. Static works which produce their kinetic ‘ effect by the movement of the spectator;

3. Works involving the projection of light;.

Works which require the participation of the spectator.

Since the twenty’s technology has sufficiently advanced to make it possible for artists to use a wide variety of electrically powered machines.

But some still rely on natural sources of power. Kenneth Martin and George Rickey, like Calder, uses the movement of air: Martin, to achieve a continuous upward spiral motion of curving metal strips; Rickey to produce contrasted rhythmic movements with tall, slender blades which move to and fro like high grass swayed by a breeze.

Other artists employ natural forces together with electrical power. Takis uses magnetism. His Magnetic Ballet consists of a large white metal ball which, alternately attracted and repelled by a magnetic coil, is compelled to perform an erratic dance around it.

Others such as Schöffer, Kramer, and Tinguely make it a part of the work. The latter solution is aesthetically more satisfying to the extent that the element of mystification is removed.

But 80 far these ‘machines’ have not been altogether satisfactory as works of Kinetic Art, that is, movement is made to serve some particular purpose and is not presented as something of interest in its own right or as a ‘ sculptural element ‘ in the sense explained above. Kramer’s works are really mechanical ballets.

The chief interest of a work by Bury is the mysterious life with which he has endowed the unpredictable movements of a cluster of nails, wires, or small wooden pegs.

In other words, a moving object may undergo so radical an optical transformation as to appear to be something quite different. Under certain conditions, the same effect may be attained by the spectator moving in front of an object.

The artistic possibilities of this optical phenomenon have been explored by a number of artists. Soto has done so, for instance, in his ‘vibration-structures’ and ‘metamorphoses’.

‘What has always interested me’, he says, ‘has been the transformation of elements, the dematerialization of solid matter.

Thus, as you watch, the pure line is transformed, by optical illusion, into pure vibration, the material into energy. ‘9 Soto achieves this effect by placing some object — a wire structure for example — in front of a moiré background.

As the spectator moves in front of the work, the moiré background breaks up the line of the wire a structure so that it appears as a series of little dots floating in space.

‘Separately’, as Soto says, ‘these things are nothing, but together something very strange happens. a whole world of new meaning and possibility is revealed by the combination of simple, neutral elements. ‘

Like Turner and the Impressionists, Soto’s aim is to dissolve form into color and light, to realize, as he says, ‘an abstract world of pure relations, which has a different existence from the world of things … My aim is to free the material until it becomes as free as music — although here I mean music, not in the sense of melody, but in the sense of pure relations.’

The works of other artists such as Vasarely, Agam, Cruz-Diez, or Asis are more pictorial. In each case, the forms alter as the spectator passes in front of them, as though one were looking at an abstract movie.

Sometimes, as in the case of Cruz-Diez’s physichromies, the colours change as well as the forms; they can range from a deep red when viewed from one end to a deep blue at the other.

Both Agam and Vasarely get their effects by designing on sheets of Perspex or some such material placed one in front of the other. Asis, on the other hand, gets his effects — usually a sort of watered silk pattern — by optical illusion, in fact by placing a perforated sheet in front of a background of dots corresponding in size to the perforations.

Though these works gain in interest by their changing pattern, they do not depend on movement in the way in which those of Soto and the other Kinetic artists we have considered doing.

It is possible at any moment to fix on a particular phase of the composition and contemplate it as one would a painted relief.

However, the fact remains that, when one does move, the composition alters in a way quite unlike that of a ‘static ‘ relief.

It is so classified because it gives a strong impression of movement. The work seems to expand and contract, advance and recede; parts appear to rotate, to leap about the canvas, to appear and disappear, etc. It does not, however, involve actual movement, either on the part of the work or of the spectator.

Hence one essential feature of Kinetic Art, as conceived by Gabo and Pevsner — the construction of some form or image in space by movement — is lacking.

The space in which the shapes appear to move is wholly illusory, unlike the space in which the works of Soto or Asis operate, which is partly illusory and partly actual.

Hence there is a case for excluding it from the category of Kinetic Art. It might be argued that to draw a line between what Soto and Asis are doing and what the Op artists do is arbitrary; the two merge into one another. But this is not true.

The Kinetic artists, on the other hand, rely on movement as a transforming element. They differ both in method and intention. To call both ‘kinetic’ would obscure important differences between them.

This use of light has the effect of drawing the spectator into the orbit of the work itself. It creates an artistic environment. But the focus of attention can vary.

In the work of Nicholas Schöffer, for instance, attention is directed more to the illuminated surfaces of the polished metal parts of the work than to the movement of the light around the walls.

In certain works of von Graevnitz, Piene and Ie Parc it is the movement of the light which is the main the focus of interest.

Piene’s ambition is to make monumental light projections out of doors. ‘My greatest dream ‘, he says, ‘is to project light into the vast night sky, to probe the universe as it meets the light.’

The use of neon, on the other hand, as it is employed by Morellet, for instance, enables the artist to map out areas of space by means of the light source itself, that is, without projection.

Neon is particularly suitable for this purpose. As the works of Garcia-Rossi and Don Mason demonstrate, it is possible to produce the most subtle changes of tempo and mood by the random illumination of neon rods.

As a spectator moves in front of a Light Relief by Mack the light reflected from the polished metal strips begin to flicker and vibrate, and the object seems to dissolve into vibrating light.

In some of Martha Boto’s works light projected through revolving metal discs gives one the impression of looking at whirling galaxies or silver dust.

In Liliane Lijn’s Liquid Reflections light is captured by droplets of water which act as a lens, magnifying, reflecting, and projecting it. The simplest elements can be incredibly transformed by means of moving light.

But there are other works such as those by Malina and Healey which are more difficult to classify in this way.

The light moves but it does not move in space. It is projected on to a screen from behind. This is what I mean by the pictorial use of light: painting with light.

In principle, this use of light is no different from that in the cinema. But if one wishes to extend the term Kinetic Art to include even films — at least abstract films such as those made by Eggling in the twenties — one runs the risk of confusing two distinct concepts.

It might be argued, however, that unlike film or television, one can, at least dimly, discern the moving parts which produce the images on the screen of a Malina or Healey.

We wish to develop in him an increased capacity for perception and action.’ 13 And speaking of their Labyrinthe, they said: ‘It is deliberately directed towards the elimination of the distance between the spectator and the work of art.

As this distance disappears the greater becomes the interest of the work itself, and the lesser the importance of the personality of the maker.’ 14 Traditionally the spectator has played a more or less, though not entirely, passive role.

Spectator participation can range from the limited activity of setting work in motion and stopping it, to actually constructing it. In this respect, Lygia Clark’s Animals offer a particularly good example.

Thus, in manipulating the work he is conscious of a certain purposiveness within it. As Lygia Clark says, a new relationship is set up between the spectator and the work.

This new relationship is made possible by the independent movement of the work in response to the action of the manipulator.

This changes the role of the artist also. He no longer offers a completed work but rather a set of possibilities, a program, a situation from which work can develop.

His attention is wholly concentrated by the surrounding darkness and the light makes an assault on his senses.

One gets this concentration of the faculties in the cinema and the theatre. But in an environment of kinetic light objects such as the Groupe de Recherche’s Labyrinlhe the spectator’s perceptions are still further heightened by the fact that he can not only activate the works but also move about within them.

Exact repetition of movement, however complex, becomes monotonous. But the completely random movement has also to be avoided, for it would be a point or form: it would be chaotic.

Some control must be exercised. This is generally achieved by finding some relationship between the elements in the work which remains constant through every variation of movement.

The number of ways in which this relationship is realized may be indefinite. It may be a matter of chance which realization occurs at a particular moment.

But because there is a constant underlying relationship, the movements have a pattern.

It is inevitable that it should be used in all sorts of different ways. This may be bewildering to the uninitiated, but it need not lead to utter confusion provided certain distinctions are made.

I have tried to indicate what these distinctions are. There are works which involve movement in space, either on the part of the work itself or of the spectator, whether he manipulates the work or not, and this ideally should involve some optical transformation of the elements of which the work consists.

Then there are works which give an impression of movement involving actual movement (Op Art); works which involve actual, though two-dimensional movement — moving reliefs and films — with or without an illusion of movement in space; and finally, static representations of movement, as in futurist paintings.

If one cares to call any or all of these Kinetic Art, well and good, but at least the distinctions should be preserved.

1. Dadaism 2. Fauvism 3. Synthetic Cubism 4. What is Art 5. Minimalism 6. Philosophy of Art 7. Banksy’s painting 8. Graffiti 9. Facts about Paul Gauguin 10. Beginning of civilization 11.Famous Quotes by Pablo Picasso 12. Leonardo da Vinci quotes 13.George Keyt 14. Gulam Mohammad Sheikh 15. female influential Artist 16. Why did Van Gogh cut off his ear 17. The Starry Night 1889 18. most expensive paintings 19. The Stone Breakers 20. Vocabulary of Visual Art 21. Contemporary art 22. What is Digital Art 23. Art of Indus Valley Civilization 24. Essential tools and materials for painting 25. Indus Valley 26. PostImpressionism 27. Mesopotamian civilizations28. Greek architecture 29. Landscape Artists 30. THE LAST SUPPER 31. Impressionism 32. Prehistoric Rock Art of Africa 33. Hand Painted Wine Glasses 34. George Keyt

1.Proto- Renaissance: History and characteristics 2. HighRenaissance 3. KineticArt 4. Purism 5. Orphism 6. Futurism 7. Impressionism: A Revolutionary Art Movement 8. Post Impressionism 9 Fauvism | Influence on Fauvism 10. Cubism | Cezannian Cubism | Analytical Cubism | Synthetic Cubism 11. Romanticism 12. Rococo: Art, Architecture, and Sculpture 13. Baroque art and architecture 14. Mannerism 15. Dadaism: Meaning, Definition, History, and artists 16. Realism: Art and Literature 17. DADAISM OUTSIDE ZURICH 18. BAPTISM OF SURREALISM 19. OPART 20. MINIMALISM