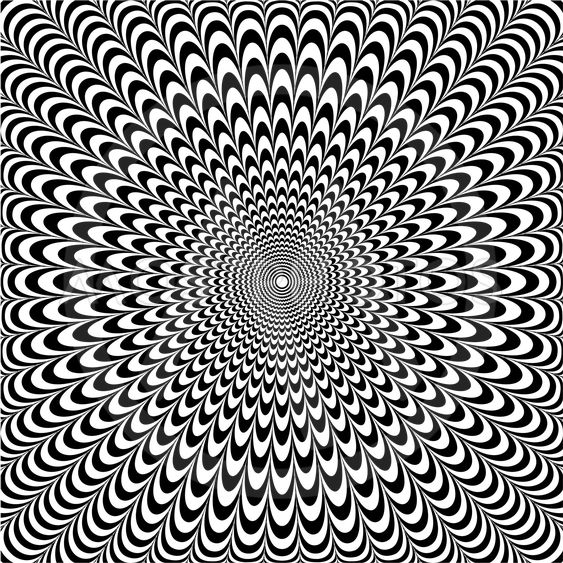

The only other generalizations which are pertinent here are that all Op Art is abstract, essentially formal and exact and that it could be seen as a development out of Constructivism and the essence of Malevich’s aim to achieve ‘the supremacy of pure sensibility in art ‘.

Furthermore, it could be seen as a trend that has been influenced by ideas developed in the Bauhaus, and those of Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers.

The organizer of the Responsive Eye exhibition (the first international exhibition with a predominance of optical paintings, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in February 1965), William Seitz, who has documented Op and other closely allied idioms since 1962, has referred to Op Art as a generator of perceptual responses.

It essentially possesses the dynamic quality which provokes illusory images and sensations in the spectator, whether this happens in the actual physical structure of the eye or in the brain itself.

Thus, one can deduce that Op Art deals in a very fundamental and significant way with illusion.

Illusion exploits the spectator’s capacity to complete images in the mind’s eye on the basis of previous experience.

It is, moreover, the process by which the imagination is stimulated to defeat the logic of two-dimensional canvas. This is the case, for instance, with trompe l’oeil.

The term Op Art, however, is applied to that type of illusion where the normal processes of seeing are brought into doubt, mainly through the optical phenomena of the work.

Coined in America, Op Art was first referred to in print in Time magazine (October 1964), and two months later was featured in Life.

By 1965 Op Art was a household phrase referring both in England and America to black and white boldly patterned fabrics, window displays, and generally utilitarian objects.

A unique aspect of the movement was its nearly simultaneous arrival on both fronts — the esoteric and the popular.

The indeterminate forms in their paintings resolve themselves chromatically as well as figuratively when the spectator steps back into a suitable position.

Whereas the pointillist technique was merely a creative approach for painterslike Seurat, Signac, Pissarro, and Cross in the 1880s, the technical aspects of Op Art is committed to a now-familiar concept in modern painting, where this the technique has, in fact, become the subject matter, and virtually the sole content of the painting.

Thus, these qualities, the technique, and the subject matter are totally indivisible.

Albers who taught at the Bauhaus, Black Mountain College and Yale, where he held his famous classes on colour, has always stressed the fact that any work which involves the use of colour is an empirical study in relationships.

He has shown how deceptive colour can be, how different colours can be made to look identical and three colours can be read ag two or conversely as four.

Among these were his chequer-board compositions with chess pieces, and paintings of subjects like tigers and zebras which acted as vehicles for striped patterns.

In all paintings since, he has employed optical ambiguity and disorientation through the use of syncopated rhythms and geometric patterns.

The black and white, colored, and more recently three-dimensional constructions are the expression of Vasarely’s idea of what should be the relationship between the work and the spectator.

The intellectual concept of understanding becomes irrelevant in a realm of art which is involved with sensation to such a degree that it creates a virtually physical effect on the viewer.

Vasarely is committed to the depersonalization of the artist’s act — he feels that works of art should become available to all and discard their uniqueness.

To his own field of activity, he has applied the term kinetic art — an art, form which is based on multi-dimensional illusion.

Whereas kinetic art implies, in the strict sense, the use of mechanical movement, kinetic art is involved with the illusionistic or virtual movement.

The term kinetic could also be considered relevant to the work of Yaacov Agam, particularly his polymorphic paintings on corrugated surfaces with patterns that fuse and change as one walks in front of them, as well as to the works of Cruz-Diez and J. R. Soto, where an illusion of movement takes place as the spectator is in motion and the work remains stationary.

Few Of the underlying theories arc supplied by the artists themselves, and furthermore, it is impossible to make any exact delineation as to where precisely the movement begins and ends.

Some kinetic works, for instance, where use is made of light effects and a certain spatial ambiguity, often touch on the borderline of Op Art.

The Groupe de Recherche d’ Art Visual from Paris works not only with mechanical movement but with the illusion of movement as well.

The classical example of the use of both types of movement is Duchamp’s rotoreliefs of 1935 — discs with circular patterns which produce the illusion of motion in perspective when placed on a gramophone turn- table.

Here the simplicity of forms and specific use of color allows the viewer to see them alternately as figures and backgrounds.

Kelly’s paintings, like those of Peter Sedgley and the pattern pictures of Larry Poons and Richard exploit the false impression engendered by the use of complementary colors and produce a powerful after image.

Although these paintings seem to belong so naturally to the Op Art movement, one must remember that Kelly, for instance, painted his chromatic figure-ground compositions already in the fifties, at a time when different aspects of his work, rather than optical ones were discussed.

This is also, of course, true of artists like Vasarely, Max Bill, Soto and Karl Gerstner among many others, whose individual pursuits suddenly in 1964 came into line with a newly named trend.

These result from the inexact superimposition of two or more sets of parallel lines, or other repetitive structures.

The almost magical effects of undulating lines with the illusion of depth and movement have been utilized by J. R. Soto, Gerald Oster, John Goodyear, Ludwig Wilding, and Mon Levinson.

The most optically dynamic works, apart from three-dimensional constructions like Karl Gerstner’s lens pictures and illusionist glass boxes by Leroy Lamis and Robert Stevenson, are those black and white paintings that seem to produce a completely unstable surface.

The most inventive painter in this field is Bridget Riley, whose undulating stripes and various formal progressions are based on intuitively conceived patterns that are developed systematically in the finished painting.

Among other artists whose paintings produce strange optical disturbances and ambiguities are the Japanese painter Tadasky who makes compositions of concentric circles which he paints on a turntable, and the American Julian Stanczak who creates abstract organic images with horizontal or vertical black and white stripes of varying thicknesses.

Their works operate on what Gombrich has called the etcetera principle. A state when the mind is tricked into seeing something which does not exist because of the physical conditions which are created.

Op paintings do not lend themselves to intellectual exploration — their forte is the provocation of an intensely sensual and often sensational impact, which ultimately can be nothing less and nothing more than a unique experience.

1. Dadaism 2. Fauvism 3. Synthetic Cubism 4. What is Art 5. Minimalism 6. Philosophy of Art 7. Banksy’s painting 8. Graffiti 9. Facts about Paul Gauguin 10. Beginning of civilization 11.Famous Quotes by Pablo Picasso 12. Leonardo da Vinci quotes 13.George Keyt 14. Gulam Mohammad Sheikh 15. female influential Artist 16. Why did Van Gogh cut off his ear 17. The Starry Night 1889 18. most expensive paintings 19. The Stone Breakers 20. Vocabulary of Visual Art 21. Contemporary art 22. What is Digital Art 23. Art of Indus Valley Civilization 24. Essential tools and materials for painting 25. Indus Valley 26. PostImpressionism 27. Mesopotamian civilizations28. Greek architecture 29. Landscape Artists 30. THE LAST SUPPER 31. Impressionism 32. Prehistoric Rock Art of Africa 33. Hand Painted Wine Glasses 34. George Keyt

1.Proto- Renaissance: History and characteristics 2. HighRenaissance 3. KineticArt 4. Purism 5. Orphism 6. Futurism 7. Impressionism: A Revolutionary Art Movement 8. Post Impressionism 9 Fauvism | Influence on Fauvism 10. Cubism | Cezannian Cubism | Analytical Cubism | Synthetic Cubism 11. Romanticism 12. Rococo: Art, Architecture, and Sculpture 13. Baroque art and architecture 14. Mannerism 15. Dadaism: Meaning, Definition, History, and artists 16. Realism: Art and Literature 17. DADAISM OUTSIDE ZURICH 18. BAPTISM OF SURREALISM 19. OPART 20. MINIMALISM