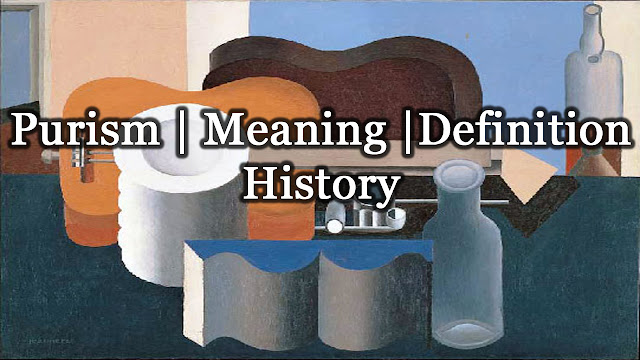

Purism | Meaning | Definition | History

Purism came after Cubism and was launched a book published in 1918, Apris Ie Cubisme. Cubism, declared its authors Amédée Ozenfant and Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier), had ended by not recognizing its own significance or the significance of the post-war epoch: it was ‘the troubled art of a troubled time’: Purism claimed it would take Cubism to its proper conclusions, those of a cooperative and constructive epoch of order.

It was a very ambitious movement, which had a brief life (seven years), and only through the architecture of Le Corbusier did it gain a large international reputation. Purist paintings were shown, within its lifetime, as far away from Paris as Prague, but the great post-war impact in painting and sculpture came from De Stijl, Constructivism, and Surrealism. The high years of the movement were the years of Theo van Does- burg’s first Parisian sermons on De Stijl, and of André Breton and Tristan Tzara (1920—25). It was, at the same time, against such competition that Purism was able to offer a genuine and independent alternative both to the post-war Cubists of the Paris School and to De Stijl.

Clarity and objectivity were central to the Purist theme, art moved ‘vers le cristal ‘. Yet Ozenfant and Jeanneret gave their declarations the repetitive insistence of prophets offering revelation: Apr&s Ie Cubisme was a passionate declaration of belief, and most of the editorial opinion of their magazine L’Esprit nouveau (1920—25) was put across manifesto force. Their final undertaking La Peinture Moderne (1925) sharpens that force. What Cocteau dubbed ‘The call to order’ was made by Ozenfant and Jeanneret with fervor, a feeling of revolutionary purpose, and a full appreciation of cultural guerrilla tactics.

Yet, the dynamism of purist publications freezes when one confronts the ideas they represent, and the calm exactitude of Purist works. The movement seems calculated to create opposition. So many of those modern aesthetic ideals least loved by popular opinion are there: the beauty of functional efficiency, the importance of intellect, the unimportance of individuals, the value of precision.

They lie behind De Stijl and Constructivism as well as Purism, but combined with them, in L’ Esprit Nouveau, is a hostility to extremes that is alien to those movements and which antagonizes informed opinion: the elemental abstractions of De Stijl make the bottles and jugs of purist still-lives seem timid: Mondrian is dramatically quiet, the Purists are simply quiet. Though mild to the informed, the movement seems extreme to the formed: it is after all Puritan and restrictive in precisely the same way as De Stijl.

The dogmatic certainty behind its campaign for order, like that of De Stijl, merely serves to emphasize, by means of the equally dogmatic reactions caused, the existence of more than one directive force in human nature. Those who believe in instinct see in a passionate declaration of the power of reason only a negation of instinct, while those who believe in reason see in a passionate declaration of the power of instinct only a negation of reason.

It is difficult to gain sympathy for Purism because it is so easy to see it for what it is not: a Le Corbusier villa too easily arouses the Borromini in us, an Ozenfant still-life, the Rubens in us. Only when we have accepted what Purism is not, with understanding rather than regret, can we begin to see and enjoy what it is.

It was Puritan, but Ozenfant and Jeanneret were not kill-joys: they distinguished between joy and pleasure and they preached the end of pleasure in art, the supremacy of joy: pleasure, they believed, is unbalanced, joy is balanced, pleasure pleasing, joy elevating, pleasure satisfies appetites, joy satisfies the need for order in life, pleasure satisfies passing whim, joy satisfies something constant in us. Their aim was to give art an unchanging foundation, and in this sense they were classical. There is in art, Purism tells us, an essential factor to which we all aspire.

That factor is Number: the way in which we are the order of numerical division in the structure of our thoughts, our work and the works of nature — proportion The past and the present is conceived of as a pyramid: at the top Of the pyramid are found all together Poussin, Ingres, Corot, Pericles Eiffel, Plato, Pascal, Einstein, etc: the implication is that Poussin. had he lived to see the paintings of L’Esprit noureau, would have admired them, just as the Purists admired his, that the quality that of great art, great living and great thinking does not change, the pyramid has the same apex in every era and every sphere.

Such hierarchical thinking implies a certainty analogous with that of Renaissance Humanism. For Daniele Barbaro, Aristotelian thinker and contemporary of Palladio, the laws of harmony in proportion represented the true laws of life, therefore science, which explored these laws and the arts which used them, dealt with certainty.

Ozenfant and Jeanneret aimed their art at a definite point, but they did not claim that in this was revealed some objectively valid Truth. Ozenfant was adamant: we cannot, he says, be certain that the order revealed to us by reason — i.e. science — exists apart from us, is more than a reflection of the structure of our own minds and senses.

But we can be certain that this order constantly found in our surroundings and our actions satisfy a genuine human need — the need of our minds to conceive equilibrium and our senses to perceive it. Science and art are proof of the constancy of this need: the Parthenon and Einstein’s equations both fulfill the same human function.

In this light, functionalism becomes a new extension of Renaissance Humanism with the emphasis on proportion, based on a retreat from God into the sphere of Man alone. The proportions which give men beauty in their thinking, in their listening and their seeing are thought of as directly related to the order of their bodies, the structure of their sense organs and of their minds, but they are no longer related to God.

Functionalism in engineering, in industrial design, in architecture, and in painting is presented altogether by Ozenfant and Jeanneret in humanist terms, and at its root lies the notion of ‘ Sélection Mécanique’.

The starting point for this notion is the same as that of the Renaissance, the human body: in itself, it is believed to reveal the older men search for. Every organ is the result of constant adaptation to functional needs: ‘One is able to ascertain a tendency towards certain identical features, responding to constant functions.’

The tendency is towards the greater and greater economy of effort as the harmony between form and function is perfected. From the human body, Ozenfant and Jeanneret move to those objects which men make solely to answer their functional needs, and find too that certain ‘objects types ‘ have been perfected to answer constant needs: glasses, bottles, etc. ‘These objects associate themselves with the organism and complete it’; they are in harmony with Man.

Architecture, engineering, industrial design are all concerned with constant human needs — for dwellings, utensils, communications thus, the logical conclusion is that a functional approach to them is humanist: the proportions of a humanist art are the proportions determined by human need.

However, by function Ozenfant and Jeanneret mean more than utility, they mean aesthetic function too, because among man’s basic needs is for them, as we have seen, the need for art. Jeanneret puts his position like this: an engineer is presented with alternative ideas for a bridge each as efficient as the others and he becomes an artist only when he selects the one most clearly harmonious in its proportions. Art is not useful but it is necessary, that is why paintings are painted and buildings are built as ‘architecture’ and not simply as ‘machines for living in’.

The machine was important to Purism but in a supporting rather than a leading role: it represented an answer, always knew, to a constant human need for order. Art, on the other hand, represented an answer, never new, to the same human need. Each new machine: no work superseded an old one and would be superseded by another of art could be superseded by another Art, we are told. is based on the unchanging physiological structure of the eye, mind, and body in response to form, line, and color.

Science and the machine are based on changing the fabric of knowledge. The machine might create L’ Esprit nouveau — a new awareness of precision and complexity within the old theme of order — but it can never be a work of art, being on the technological plane alone, because it can never be of constant value in an advancing technology.

A grammar and syntax of sensation is elaborated by the Purists as the foundation of art. Form, line and color are seen as the elements of a language that does not change from culture to culture because it is based on invariable optical reactions. The Purists are strict rule-makers: their focus is on constant factors. Therefore color (seen as a surface factor) is subordinated to form, whose integrity it can so easily destroy, as, for instance, in Impressionism.

Form itself is categorized as either primary or secondary, either capable of a constant the effect, free of secondary associations, or not: a cube carries the same ‘plastic’ meaning for everyone, while a freely spiraling line might make one man see snake and another a whirlpool. Primary forms are established as the basis for composition, disciplined by the invariably stable dominance of the vertical and the horizontal, and composition is defined as a secondary elaboration on a primary formal theme.

So full a development of a formal language and so strong an emphasis on the abstract ideals of harmony and precision might seem to lead somewhere very different from the bottles and guitars of purist paintings: a strictly architectural painting seems at first the most logical result — an elaborated but muted version of De Stijl. Yet, Purism’s insistence on the old subject-matter of Analytic and Synthetic Cubism is no compromise; it, too, is the result of a strict investigation of the means and ends of art.

The subject-matter of their still-lives, in fact, binds the humanism of Ozenfant and Jeanneret into a complete whole, putting their painting into direct contact with the practical world of engineering and ‘objets types‘, constructing a bridge between the practical and the aesthetic spheres. An art which did no more than elaborate on primary formal themes was, for the purists writing in L’ Esprit Nouveau, merely ornamental; it lacked something which they defined in La Peinture Moderne as ‘an intellectual and affective emotion’ expected of art.

That emotion was called ‘passion’ by Jeanneret in the articles on which his internationally influential book Vers une Architecture was based. ‘Passion ‘ was the artist’s ability to grasp the order intuitively in the disorder of his surroundings, to find art in the material world of natural and man-made objects.

The scientist could construct beneath the chaotic surface of nature an intricate and balanced system of laws; the artist was so gifted that he could intuitively discover objects in the external world that demonstrated such a system outwardly in their form. The bottles and guitars of Purist paintings are therefore objects in which order has been found. The qualities of that order are clear, for the objects of Purist paintings are of course ‘Objels types’. They are the qualities of a humanist functionalism: the qualities that follow from absolute efficiency—precision, simplicity and proportional harmony.

From the Purist viewpoint, there was about the ‘object type’ a banality which placed it above the human figure as the subject of great art: the human figure too easily appealed to particular feelings: the ‘objet type’, so common that it was hardly noticed, free of all Possible literary associations could never appeal to such feelings — it is difficult to lust after a bottle. Thus, the ‘objet type’ joined the generalized, formal emphasis essential in art, to the material world without danger of distraction, and it is, in the final analysis, the Purist approach to the object that demonstrates conclusively Purism’s independence from both De Stijl and Cubism.

Ozenfant and Jeanneret dismiss pure abstraction for its lack of ‘passion ‘, just as they dismiss the photographic realism of Meissonier for its lack of structure and they give a new clarity to the cubist method of shift- ing viewpoint analysis. Like the ideal cubist following the rules of Gleizes and Metzinger’s 1912 Du Cubisme, they shift viewpoint in order to move from one ‘essential’ aspect of an object to another, from, say, the circular base of a glass [illustration 28] to its tapering profile, to its circular top, thus translating it into a simple formal theme. A firm grip is kept on their ‘objet type’ starting point and in this way the practical order of functional efficiency is joined to aesthetic order: cubist method loses all trace of ambiguity: it becomes the instrument of a philosophy as all-embracing as De Stijl, but independent of it.