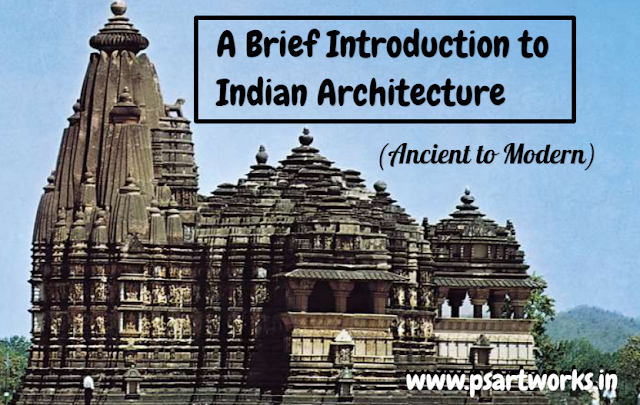

A Brief Introduction to Indian Architecture (Ancient to Modern)

Whole cities have been excavated, and a range of artefacts found, but much of the civilization still remains a mystery because its script has not yet been deciphered.

However, the statuettes, seals and other implements found tell of an agrarian society which worshipped, amongst other things, the concept of fertility.

This civilization had trade and other links with contemporary civilizations of the west, contacts being maintained by caravans traveling through mountain passes of the Himalayas.

The Arrival of Hinduism

The Indo-Aryans were pastoral. They worshipped fire and had anthropomorphic gods and well-established rituals of prayer which were coded in a set of oral texts called the Vedas, which only assumed a literary form 500 years later.

Their religion eventually came to be known as Hinduism. The Aryans settled down in the fertile plain of the Ganges River, subjugated the native tribes, and started the process of cultural assimilation that has been one of the hallmarks of the Indian sub-continent’s history.

Unfortunately, even though literary texts provide us with some evidence of the architectural activities of the time, no archaeological evidence remains.

Buddhism was founded in the 5th century BC, and received royal patronage 200 years later under the Mauryan king Ashoka, who converted to the faith after a bloody battle fought against the king of Kalinga (in Orissa) on the eastern coast of India.

It was around this time that Alexander of Macedonia reached India, and though he eventually did not succeed in extending his empire to this part of the world, his invasion brought the tradition of stone carving to the Indian subcontinent.

Proof that prior to this period Indian architecture had a strong, well-developed tradition of building in wood, bamboo, and thatch is available in the forms created in stone by Ashoka’s architects and craftsmen.

All the architecture of the period shows that wooden structural forms, especially those of column, beam, and lintel, were being replicated in stone.

The Mauryas and the Guptas

A sound administrative system, clear-cut social order, peace, and security established a firm foundation that led to the rule of Ashoka, a great and visionary emperor.

Although he ruthlessly expanded his kingdom during the first eight years of his rule, Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism thereafter caused him to espouse non-violence while maintaining a pragmatism in all matters of governance.

Only the most southernmost kingdoms of the peninsula remained independent while Ashoka’s empire extended across the length and breadth of the rest of India.

The extent of his kingdom is evident from the thousands of stupas, pillars, and rocks bearing Buddhist edicts erected by Ashoka.

His legacy lives on in the Sarnath pillar decorated with four lions that has been adopted as an emblem of independent India.

During the era of the Guptas also referred to as the Golden or Classical Age, the Hindu temple, in particular, acquired an ornate image with the embellishment of extravagant sculptures.

The Earliest Architectural Traditions

Later, the caves excavated by these monks were cut into to create ornate interiors. Gradually, the transition from rock-cut to stone-made architecture took place all over the subcontinent, and the monumental architecture of this period, built to survive through time, is all stone-cut or stone-made.

St Thomas had reached the southern shores of India in AD 52, and some churches may have been built, but again no evidence remains, and the predominant monumental architectural activity in’ the subcontinent at this time was inspired by Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism.

The iconography of all three religions began to show a fair degree of synthesis of content and form, and many elements originating in one religious tradition were adopted by the others, once again demonstrating the inherent secularism within each diverse cultural traditions.

Racially and linguistically, however, there were the two major groupings of northern Aryans and southern Dravidians, but there also existed many other indigenous tribes in the eastern, northeastern and central regions with their own distinct cultural identities.

Central and North Indian Kingdoms

The constant conflict eventually depleted their resources, resulting in their decline.

In fact, it can be generally said that perhaps in no other art as much as in architecture did religion play such a pivotal role in forming stylistic identities and associations, enhanced by India’s artistic energies to absorb varying influences.

Eastern Renaissance

A unique style of temple architecture flourished in Bhubaneshwar, the artistic and religious capital of the region, which eventually merged in the south with the Dravidian forms and spread its influence westward toward Rajasthan.

Beyond Bhubaneshwar, Konarak and further east, the terracotta temples of Gaur and Vishnupur, Bengal, both add brief but glorious chapters to the history of Hindu architecture’s development north of the Vindhya range.

The Advent of Islam

Later, in AD 1192, on the country’s northern frontiers, Mohammad Ghauri, a Turkish warlord from the steppes of Central Asia, advanced deep into the region and overthrew the Rajput king Prithviraj Chauhan, marking the political entry of Islam in India.

Islam itself had touched India in the 8th century AD through Sind on the western shores, but it was only in the 12th century AD that a dynasty was established that had a different religious identity to the prevailing faith.

The Mamluk or Slave dynasty was the first of the Muslim dynasties to be established in India, where it maintained its strong identity of culture and religion.

They also introduced a new form of decoration, based on geometry and calligraphy, into the already present iconographic imagery of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Over the next 700 years, art, architecture, music and literature saw a synthesis of traditions from all these religions and the creation of a distinct style of aesthetics.

The uneasy truce between these Islamic kingdoms and the established Hindu kingdoms was broken occasionally. Architecturally, however, the cross-influence of both cultures proved to be both invigorating as well as long-lasting.

The Great Mughals

Akbar’s political policy of integrating disparate elements and forging alliances with Hindu Rajput kings, who had earlier been sworn enemies, was reflected in the aesthetic idiom that was created under the Mughals, with the fusion of Persian, Muslim and classical Hindu styles.

The high point of Mughal architecture is, of course, the Taj Mahal, but each of the six great rulers of the dynasty can lay claim to memorable buildings and works of art.

The East India Company

Vasco da Gama had already landed at Calicut in southern India in 1498, and tales of India’s wealth had reached almost all parts of the world, including Europe.

The Portuguese, the Dutch, the French and the British all wanted to establish colonies in India, although their motives ranged from the religious to the economic.

The trade and other links between various European powers and Mughal India led to the British establishing the East India Company, which eventually extended its commercial interests to play a more political role in the subcontinent.

By 1857, the last Mughal emperor had been deposed by the British, who had brought most of India under the dynasty’s domination. Finally, India was declared to be a colony of Imperial Britain.

Broadly classified as the Colonial style, this became a hybrid manifestation of new and old structural forms and decorative elements. Public institutions such as railway stations, post offices, and administrative centers entered the realm of building.

Domestic architecture was typified by the bungalow. For nearly 5,000 years, the Indian subcontinent had lured outsiders who came to conquer but stayed and merged their identities and became a part of India.

The British, however, remained outsiders, and their economic and political exploitation of the country finally ended in 1947 when India became independent.

India’s struggle for political freedom was largely peaceful even though independence was gained after the traumatic partition of India and the creation of Pakistan.

Residential Spaces

Public and private areas were separate, and women kept protected from the public gaze.

The internal courtyard was the center, restricted to family members, with rooms opening out on either side, ensuring privacy to their inhabitants.

North India: The Haveli

Often built on narrow streets, the outer walls of larger Havelis rose 3-4 stories high, casting shadows on their neighbors. Interiors thus remained cool. The narrow streets also acted as wind funnels, further cooling the buildings.

It signified the transition between the public space outside the house and the private or personal space within.

This was a totally male domain into which women rarely entered. The baithak opened out into another room, beyond which, completely shielded from the gaze of strangers, was the central courtyard.

Rooms on the upper floors also had canopied balconies called jharokhas looking down into the street.

Shielded by carved stone latticework screens (jaalis), they allowed the inhabitants to look out without being seen, and also served to break the force of hot winds, allowing the interiors to be airy.

There was usually a teh khana or basement, which was the cool retreat of the house and also the place where valuables were stored. Security was, in fact, a major determinant in the plan.

Doors had low lintels and high thresholds, probably to ensure that an unwelcome person could not enter easily. The staircases, too, were twisted and narrow, with uncomfortably high risers.

Owners of Havelis vied with each other to create opulent mansions with painted interiors and ornate stone-and woodwork.

South India: The Kerala House Homes in Kerala follow rigid systems of planning and orientation. The generic Kerala house is known as the nalukettu, nalu meaning “four” and kettu meaning “courtyard.” The house thus comprises four blocks around a courtyard.

Based on this principle, the nalukettu is surrounded by a deep, covered verandah, whose inward-sloping roof rests on a pillar at each commer.

Rooms are arranged around the verandah in a linear fashion. The roof is pitched and extends over the exterior walls to cover another verandah, usually in the front portion of the house.

The four blocks of the tarawad must be oriented in the cardinal directions around a central courtyard known as the nadumuttam.

The main entrance leads into a lobby or enclosed verandah, with a pair of windows opening through three arches giving onto the true verandah.

The raised floor is paved with stone tile or colored lime plaster. Here stands a kinathara, a platform some 0.6 meters above floor level-a combined prayer area and sitting space.

The rooms become plainer and more functional as one passes toward the women’s quarter at the back, the most private part of the house. From one side of the semi-private lobby, stairs ascend to the finest room, the Mamallapuram.

Vernacular Architecture

Just as political and historicm events were major factors in shaping monumental buildings in India in the past, so geography, social customs, local materials and, above all, the climate have been important influences on the forms of personal living spaces.

The kachcha building is one that is made from short-lived natural materials such as mud, grass, bamboo, thatch and sticks and its form is dictated by the practical limitations of the material.

Structures made with these materials have a short life and require constant upkeep and replenishment, not only in hostile weather conditions but throughout the year.

Such structures, while being stronger, are much more expensive to build. As villagers’ earnings increase, vernacular building, mainly confined to rural locations, combines these two types to create the semi-pukka structure.

The dream of every villager is to finally own a pukka home although the kachcha structure has its own beauty, derived less from decoration (which is common due to religion or superstition) and more from its pure, practical shapes.

Diverse Materials

A variation consists of a timber frame and bonding, with the space between columns filled with random rubble in mud mortar till the sill level and then with finer stonework.

Wooden beams and rafters support roofs made of locally available slate tiles which are sloping, to drain off rain or snow.

They are made of stone slabs supported on a metal framework. Walls are made of either mud or sun-baked brick, and plastered on the inside and outside with mud mixed with hay, chaff and cowdung, and sometimes whitewashed with lime (also considered a

Thatch from various plants-coconut, paddy, elephant grass-is widely used all over the country as roofing material. In the south, clay tiles are the most common pukka roofing material.

The Structural material for construction in the south is usually casuarina or the coconut palm, good for roofing and roof beams. Floors can be either compacted earth, or laid with stone.

Clay flooring with a traditional, painstakingly prepared red laterite polish is also commonly used in the south.

Variations in Form and Infrastructure

This ensures safety for the livestock as well as warmth during the cold winter season.

In many houses, a verandah runs along one side of the house, and on the upper floors this verandah projects out, resting on brackets or corbeled out. The attic is used to store grain, root vegetables, chilies and corn.

Thick mud walls allow for windows and doors to be inset as well as for simple stone slab shelves to be fixed.

Elements of Space and Decoration Modernity is but one of the many overlays that constitute the complex canvas of Indian lifestyles, and in every region the architectural features of buildings have deep cultural resonances of older ways of living.

Traditional homes in India share certain spatial and ornamental elements which are common, regardless of where they are located The names of these elements may vary according to the region but their function and character are accepted as indispensable to domestic architecture, just as the zenana (women’s quarters) was essential for reasons of purdah and distinct from the mardana (spaces restricted to men).

The Courtyard

Present even in the earliest homes of the Indus valley civilization, the courtyard is the major spatial element of homes in the plains.

In Hindu households, there is a tulsi plant (holy basil) at its center, revered for its healing powers. It is usually contained within a plinth or ornate planter.

The Threshold

Footwear is removed at this point, and one enters the house barefoot.

The Hearth

The area around the chulha is ritually washed before the preparation of the morning meal, and it is essential to bathe before entering it.

The women of the house do all the cooking and serving. At all meals, the men are served first, sitting on low wooden stools called chowkis.

Sometimes, a second chulha was constructed in the courtyard for boiling water and other purposes.

In some tribal houses, the apex of the roof was open to the sky and covered by a clay pot that could be lifted when required.

Decorative Elements

This ritual decoration, called kolam, rangoli, or alpana, whether done daily or for special occasions, is evident throughout the country, although the patterns executed differ from place to place.

Walls are also painted or molded in relief with both geometric and iconographic motifs.

Kutch homes are covered with such ornate niches. The ornamentation in larger Hindu homes depicted entire scenes, involving figures and deities from mythology, the epics, and stories from the Puranas.

Usually the location and the subject of the paintings followed a set order. Entrances had auspicious symbols painted on them.

The colors used were earth colors. Communities of fresco painters traditionally trained in the art were employed to execute elaborate designs by wealthy patrons.

1. Dadaism 2. Fauvism 3. Synthetic Cubism 4. What is Art 5. Minimalism 6. Philosophy of Art 7. Banksy’s painting 8. Graffiti 9. Facts about Paul Gauguin 10. Beginning of civilization 11.Famous Quotes by Pablo Picasso 12. Leonardo da Vinci quotes 13.George Keyt 14. Gulam Mohammad Sheikh 15. female influential Artist 16. Why did Van Gogh cut off his ear 17. The Starry Night 1889 18. most expensive paintings 19. The Stone Breakers 20. Vocabulary of Visual Art 21. Contemporary art 22. What is Digital Art 23. Art of Indus Valley Civilization 24. Essential tools and materials for painting 25. Indus Valley 26. PostImpressionism 27. Mesopotamian civilizations28. Greek architecture 29. Landscape Artists 30. THE LAST SUPPER 31. Impressionism 32. Prehistoric Rock Art of Africa 33. Hand Painted Wine Glasses 34. George Keyt

1.Proto- Renaissance: History and characteristics 2. HighRenaissance 3. KineticArt 4. Purism 5. Orphism 6. Futurism 7. Impressionism: A Revolutionary Art Movement 8. Post Impressionism 9 Fauvism | Influence on Fauvism 10. Cubism | Cezannian Cubism | Analytical Cubism | Synthetic Cubism 11. Romanticism 12. Rococo: Art, Architecture, and Sculpture 13. Baroque art and architecture 14. Mannerism 15. Dadaism: Meaning, Definition, History, and artists 16. Realism: Art and Literature 17. DADAISM OUTSIDE ZURICH 18. BAPTISM OF SURREALISM 19. OPART 20. MINIMALISM